|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

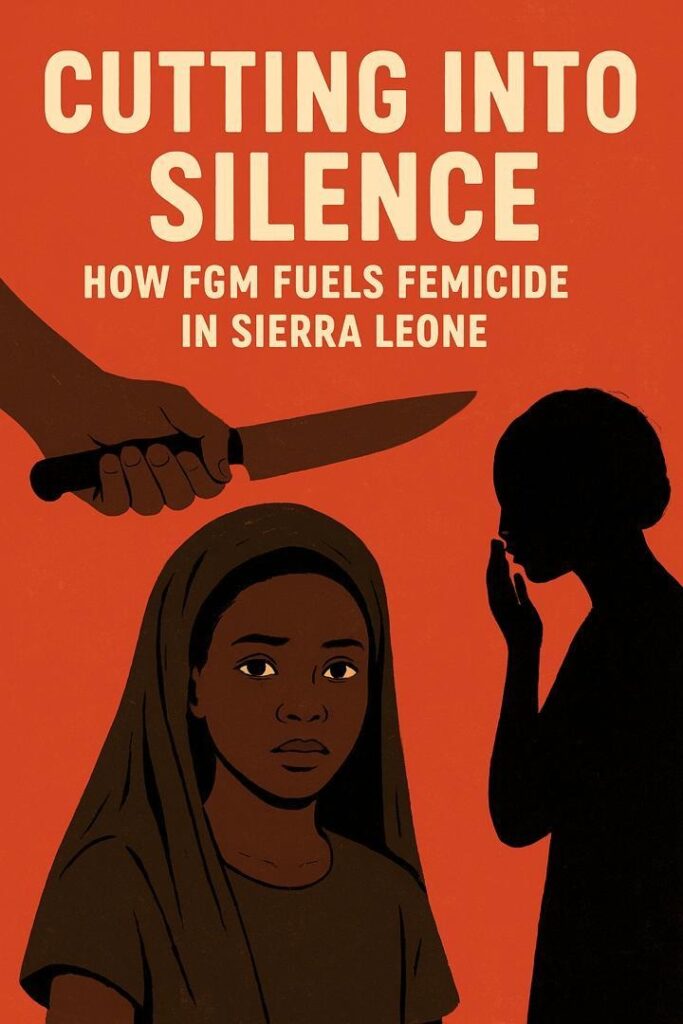

Summary

In Sierra Leone, Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) acts as a foundational ritual that teaches girls to accept pain and silence, creating a cultural continuum of normalised violence against women that fuels and perpetuates femicide.

In Sierra Leone, the violence that shapes many women’s lives begins long before anyone raises a hand. It often starts with a blade, in a ritual that teaches girls that pain is part of being female. For some, Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) is not only a physical scar but a deeper lesson in submission, a message that their bodies do not truly belong to them, and that silence in the face of suffering is expected.

This early experience of control and silence does more than harm the body; it shapes the way women navigate the world. Pain becomes familiar, voices are hushed, and a society that tolerates such rituals creates the conditions for abuse to escalate, sometimes ending in death. To understand femicide in Sierra Leone, we have to see it as part of this continuum, where culture, fear, and silence converge to make violence against women not only possible but accepted.

The Cultural Roots of Violence

FGM is a harmful cultural practice affecting millions of women and girls worldwide. It involves the partial or total removal of external female genitalia for non-medical reasons and is recognised by organisations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) as a violation of human rights. Despite global efforts to end FGM, the practice remains widespread in parts of Africa, with over 80% of women aged 15 to 49 in Sierra Leone having undergone the procedure.

In Sierra Leone, FGM is closely tied to the Bondo society, a women’s secret society. Traditionally performed at a girl’s first menstruation, the practice has adapted to include infants and adult women due to evolving laws and secrecy. Conducted in the forest by practitioners called “sowies.”

Membership in the Bondo society is often essential for social acceptance, marriage, and community participation. But we must ask: what kind of identity demands that girls bleed to belong? What kind of empowerment starts with mutilation?

While society passes down valuable cultural knowledge and life skills to women, the deep social and traditional meaning attached to FGM makes it difficult to end. The practice is often defended as a rite of passage, a way to preserve identity and belonging. Yet beneath that cultural layer lies a struggle over control.

Just as femicide is often justified by the belief that men have ownership over women, the idea that a man has the right to control, harm, or even take a woman’s life, FGM is defended by the notion that a girl’s value depends on her obedience and conformity. Both are rooted in the same foundation, a system where power over women’s bodies is disguised as culture, and where pain is passed down as tradition.

A girl who learns to endure the cut without question grows into a woman taught not to question the pain of marriage, abuse, or violence. When she is beaten, she is told to endure. When another woman is killed, she is told it’s a “family matter.” Thus, the violence of FGM fuels the broader acceptance of gender-based harm that makes femicide possible and, tragically, acceptable.

The Continuum of Violence

Femicide is not an isolated act; it is the culmination of normalised violence. FGM marks the beginning of that continuum. The girl who is cut is made to believe her suffering is sacred, and so when that same girl, years later, faces an abusive husband, she endures in silence and sometimes, until death.

Experts from Advocacy groups such as RAINBO Initiative, Forum Against Harmful Practices Sierra Leone (FAHP SL), Amazonian Initiative Movement (AIM), and Purposeful emphasise that some women who undergo FGM often experience lifelong trauma, infections, and reproductive health complications. Yet beyond the physical harm lies an even deeper social one, the conditioning to accept gender-based violence as destiny.

Sierra Leone has signed several treaties that call for the elimination of harmful practices and the protection of women, including the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, the Maputo Protocol, the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 5.2.1, and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. These commitments obligate the country to safeguard women’s bodily integrity, health, and safety, and to eradicate practices that perpetuate violence and discrimination.

Despite these international commitments, FGM continues to be widely practised in Sierra Leone, and gender-based killings often go unreported due to persistent gaps in data collection, law enforcement, and accountability. This early cultural conditioning forms the silent foundation of femicide in the country. When a woman’s pain is ritualised from childhood, her suffering and even her death can too easily become accepted as part of the norm.

The Silence that Kills and the Need to Name Femicide

Sierra Leone has made important progress in advancing gender equality. Laws such as the Domestic Violence Act of 2007, the Devolution of Estates Act of 2007, the Registration of Customary Marriage and Divorce Act of 2007, the Hands Off Our Girls campaign, and the Sexual Offences Act of 2012, later strengthened by the Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act of 2019, were critical steps in protecting women from abuse and discrimination. More recently, the Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment (GEWE) Act of 2022 and the Child Rights Act 2024 have shown a growing national commitment to women’s and children’s rights.

Yet, these laws and initiatives mean little if women continue to die without justice or recognition. When police record a woman’s death simply as murder, manslaughter, or assault, without acknowledging the gendered motive, they erase the context behind the statistics. This overlooks the patriarchal structures that normalise male dominance, control, and violence against women.

Failing to name these killings as femicide is itself a form of institutional silence. It renders countless women invisible even in death and allows a culture that devalues their lives to persist.

Breaking the Blade and the Cycle

Ending femicide in Sierra Leone requires confronting FGM not as a cultural matter but as a national emergency. To make real progress, the country must outlaw FGM and promote alternative rites of passage that celebrate empowerment instead of harm. These new approaches can preserve tradition while protecting girls, proving that womanhood does not have to be defined by pain.

One such initiative in Moyamba has already shown that cultural practices can evolve without losing their meaning. However, for these efforts to succeed on a larger scale, the government, civil society organisations, and international partners must work together to support traditional leaders and initiators. They need guidance on passing down values that uplift rather than wound, teaching human rights, health, gender equality, and the dangers of gender-based violence as part of the knowledge shared with the next generation.

Also, the state and civil society must continue to protect whistleblowers and survivors while amplifying the voices of women who speak out against FGM. When women are supported in breaking the silence, they become agents of change, inspiring others to resist harmful traditions and demand justice. Legal reform and social awareness alone are insufficient if the culture of silence persists.

Alongside, it is essential to invest in education and community dialogue, particularly with traditional and religious leaders, who are often the custodians of culture. By engaging them, communities can begin to challenge the myths and norms that uphold FGM and broader gender-based violence, replacing harmful traditions with empowering practices that protect girls from lifelong trauma. At the same time, raising awareness about existing laws that protect women is crucial, as many remain unaware of their rights or how to access justice. Public education campaigns, school programmes, and community workshops can equip women with knowledge and confidence to demand accountability when their rights are violated, ensuring that legal protections are not just words on paper, but active tools in people’s lives.

Accurate data is essential for addressing gender-based violence, and while Sierra Leone collects information on domestic violence and other forms of abuse, there is no system that specifically tracks femicide. Without data on women killed because of their gender, the full scope of the problem remains hidden, and accountability and justice are limited. Establishing a National Femicide Observatory, led by the Ministry of Gender and supported by civil society and international partners, could monitor cases, track investigations, and ensure systematic follow-up, providing the transparency needed to hold both perpetrators and institutions accountable.

Equally important is that Sierra Leone must name the crime. Parliament should recognise femicide as a distinct offence under the law, as has been done in South Africa and Kenya. Legal recognition matters because it changes how gender-based killings are recorded, investigated, and prosecuted. Without acknowledging femicide as a separate and serious crime, even the strongest existing laws will remain insufficient to protect women and bring perpetrators to justice.

To fully address the problem, the police and judicial officers must receive specialised training to identify and investigate femicide. Media institutions must also play their part by reporting these deaths accurately, rather than framing them as “lovers’ quarrels” or minimising the gendered nature of the crime. Journalism should reveal the truth, not excuse violence, and FGM must be reframed as a human rights violation that is directly connected to the wider spectrum of gendered harm, including femicide. Recognising this link makes it clear that cutting girls is not merely a cultural rite, but the first step in a continuum of harm that can, and often does, result in death.

A Call for Moral Reckoning

Sierra Leone cannot continue to celebrate women’s empowerment while ignoring the bleeding girls in the bush. The same society that praises the “Hands Off Our Girls” campaign still hands girls over to the knife. This contradiction weakens every effort toward equality.

We must speak plainly: a country that allows the cutting of girls ‘ genitals is a country that has accepted violence against women as culture. And until that changes, femicide will remain not just an act of individual cruelty, but the expression of a society’s silent consent. The blade may mark the beginning, but our silence ensures the end. It’s time to break both.

Editor’s Note: This story was produced as part of the requirement for the NFM 2025 Editorial fellowship. Naija Feminists Media is an organisation advocating for women’s rights in Africa.