Summary

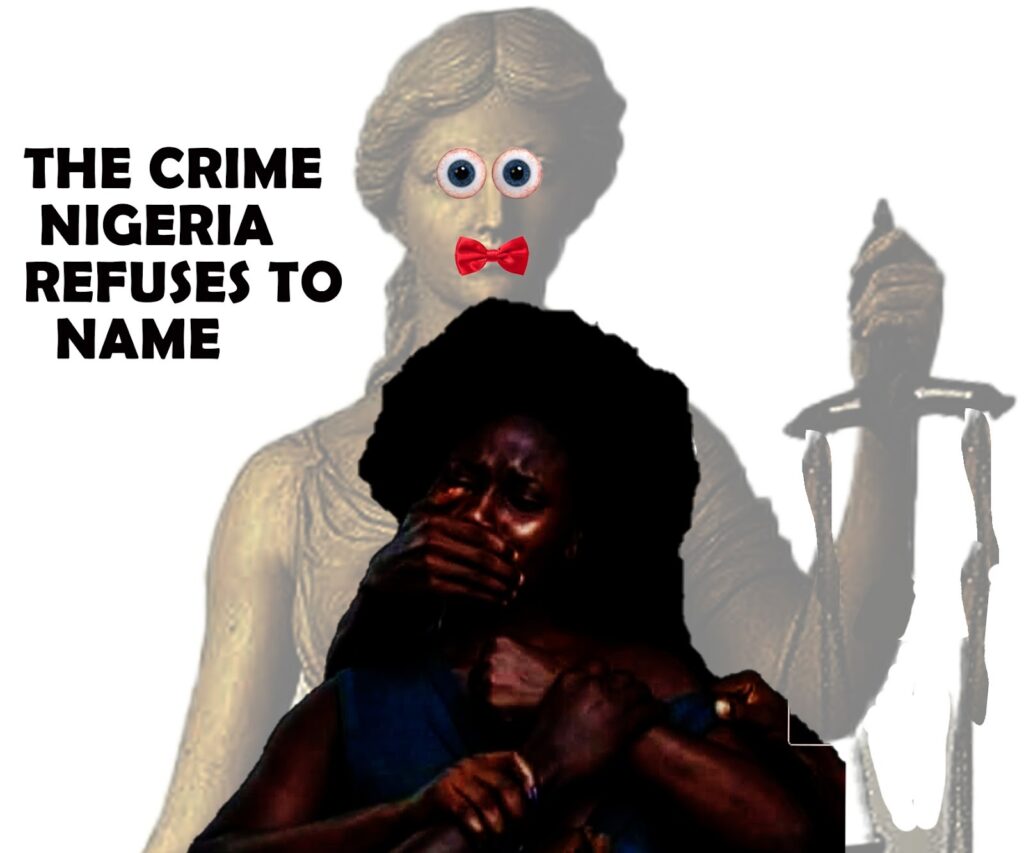

Nigeria's refusal to legally recognise "femicide" as a crime is causing the systematic misclassification and erasure of gender-motivated killings of women, leading to failed justice and perpetuating a cycle of violence.

“Silence, they say, is an old accomplice.” In Nigeria, that silence has become a weapon, one that helps bury the truth each time a woman is killed simply for being a woman. In the country, Women are being killed in gender-motivated attacks; 401 women lost their lives to sexual and gender-based violence in 2022, 149 deaths in 2024, and as of 2025, the DOHS Femicide Dashboard has recorded 19 deaths. But because the law has no name for femicide, their deaths vanish into police files, cultural silence, and legal loopholes.

Women are dying in patterns too consistent to ignore, yet the legal system treats each death as an isolated “domestic dispute” or a “relationship misunderstanding.” The killings have a name globally: femicide, the gender-motivated killing of women by men. But in Nigerian law, the term does not exist.

Because the law refuses to name the crime, the justice system routinely fails to see it. Across police stations, the death of a woman at the hands of a partner is quickly recorded under vague classifications such as manslaughter, domestic incident, or family conflict. This early mislabeling shapes the entire legal process, weakening investigations, collapsing prosecutions, and erasing the gendered nature of the violence entirely. Lawyers and gender-based violence (GBV) advocates say the consequences are deep. Nigeria cannot fight what it refuses to legally define.

Legal Implications: How Misclassification Affects Justice

In an interview, Barr. Dogo Joy, a private lawyer, FIDA volunteer, and founder of She Resonance, explained how the absence of a femicide law affects every stage of justice:

“In Nigeria, the law does not recognise femicide as a special case of concern; it only recognises murder and often misclassifies cases of femicide as murder or manslaughter. This inaction affects the quest for justice because femicide is a pattern that calls for urgent attention. If it is not recognised, you cannot develop workable solutions.”

She pointed out that globally, 25 per cent of women are killed by a present or past partner, a reality that underscores the urgent need for a systemic response.

Digital Platforms: A Crucial but Often Silenced Space

While the law remains silent, digital platforms have become one of the few spaces where advocates can speak about femicide. Yet even there, new obstacles appear. Barr. Joy referenced the case of Ochanya Ogbanje, the 13-year-old whose death initially faded from public attention but was later brought back into focus through social media. Online advocacy and sustained posts forced renewed scrutiny, ensuring the case received proper attention and investigation.

“Without sustained public pressure, many cases would disappear before the first court date,” Joy said. Online attention compels police to investigate thoroughly, prosecutors to stay engaged, communities to confront uncomfortable truths, and lawmakers to respond to public demands.

However, another barrier comes from Big Tech. Platforms like Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), Instagram, and TikTok frequently shadow-ban or suppress posts containing GBV-related words such as rape, sexual assault, violence against women, and femicide. Automated filters often reduce the visibility of these posts or remove them entirely.

This algorithmic censorship mirrors the silence embedded in cultural and legal systems. When essential terms are muted online, survivors, journalists, and activists struggle to build awareness or mobilise public outrage.

“When you refuse to call a crime what it is, or when the system hides the words we need to describe it, you help society pretend it isn’t happening,” Barr. Joy said.

The Legal Gap and the VAPP Act’s Limits

Even when tools exist to protect women, they are not evenly available. The Violence Against Persons Prohibition (VAPP) Act, Nigeria’s most progressive legislation against GBV, is in effect in some states but not in others.

Uneven domestication creates a patchwork of protection. In states that have not domesticated the VAPP Act, families are forced to rely on outdated penal codes that do not recognise patterns of gender-based violence at all. Even where the Act exists, police officers are often unaware of what the VAPP covers or how to apply it. The biggest challenge is that the law itself does not recognise femicide as a pattern of special concern. As a result, the fate of a woman killed by her partner often depends more on where she lived than on the facts of her case.

Why Naming the Crime Matters

To Barr. Joy and many feminist advocates, the refusal to name femicide is not a small technical omission; it is a national blind spot with devastating consequences. Recognising femicide in law would transform the justice system in three critical ways:

1. It forces police to investigate differently.

Officers would be required to collect evidence showing intent, history of abuse, and established patterns. Women’s deaths could no longer be dismissed as “domestic issues.”

2. It changes how courts interpret violence.

Judges would be guided by a definition that acknowledges gender-motivated killing, reducing the tendency to downgrade charges to manslaughter.

3. It reshapes public understanding of violence against women.

When the law names a crime, society must confront it. Legal clarity around rape has shifted cultural attitudes; acknowledging femicide would reframe how Nigerians understand the killing of women.

“There can never be full justice for femicide; no punishment can equate the irreplaceable loss. But that is why we need proactive measures instead of waiting for another woman to be killed before taking action,” she said.

Urgent Reforms Needed

Barr. Joy outlined several reforms necessary to protect women and secure justice:

1. Adopt a national femicide law.

A legal definition would standardise investigations, empower prosecutors, and give judges a clear framework.

2. Ensure nationwide implementation of the VAPP Act.

States that have not domesticated the Act leave women dangerously unprotected.

3. Train law enforcement on gender-based violence.

Police must understand the signs and patterns of femicide to avoid early misclassification.

4. Work with digital platforms to prevent GBV-related shadow-banning.

Advocates need safer, clearer pathways to speak about femicide without suppression by algorithms.

5. Support survivors and families.

Women’s rights organisations, including FIDA, are available to take up GBV and femicide cases. Barr. Joy encouraged individuals to “use Google to find the women’s rights groups near them and report cases immediately.”

“The law must become proactive rather than reactive. We need social awareness campaigns, digital engagement, and legal recognition of femicide as a special issue of concern,” she said.

These reforms are not bureaucratic luxuries; they are life-saving measures. Every day the law refuses to name femicide, another woman’s death risks being erased. In the absence of recognition, the killings continue uncounted, misclassified, and underreported.

When the law names the crime, Silence can no longer rhyme.

Editor’s Note: This story is produced in fulfilment of Naija Feminists Media Editorial Fellowship, and is a part of its commitment to ending male violence against women and girls in Nigeria.