For many schoolgirls with disabilities, rags are alternatives to pads

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Ahead of her 5-day menstrual flow, Precious Ejiofor*, a student with autism spectrum with flexion of the wrist, struggles to fold clothes into reasonable sizes for her menstrual flow as she cannot afford to purchase sanitary pads. While attaching a pad to her panties might be less cumbersome, folding the clothes into various shapes is a more significant struggle due to her condition.

If she forgets to fold the clothes in advance, Ejiofor risks being stained in school at the Atundaolu School for the Physically and Mentally Challenged in Lagos. When this happens, she often skips school during her period, hoping that any embarrassment from being stained will be forgotten by the time she returns.

In Nigeria, single-use menstrual pads are a common menstrual product, with households spending N184 billion as of 2021 alone. However, many girls of school age, especially those from economically disadvantaged backgrounds and those with disabilities, resort to using unhygienic alternatives due to the high cost of sanitary products.

This situation is worsened by inadequate Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) facilities in schools, which lack gender-segregated toilets, sufficient water supply, and provisions for menstrual hygiene management. These may result in absenteeism, reduced concentration in class, and low participation in extra-curricular activities.

When school girls can’t afford menstrual products, they use cheaper unhygienic options like old clothes, toilet paper, foam (from mattresses), and old newspapers.

For many girls with disabilities who are from poor families, purchasing single-use sanitary products is a tall order as they can barely afford it. In certain instances, the girls prioritise feeding over purchasing sanitary products.

Data viz –Sanitary pad is a luxury for many girls with disabilities

Goodness* Obiegwe’s first orientation about managing her menstruation was a session with her petty trader mother, who taught her how to cut and fold old clothes (rags) into different sizes to fit in as a replacement for a sanitary pad.

Obiegwe, a 16-year-old Deaf student at Sango Junior Secondary School, Agege, finds it uncomfortable to wear clothes. She now alternates between pieces of clothes and pads whenever she can afford them.

“I don’t like the old clothes that I use as a substitute but since I don’t have a choice, I have to use them. There are times I use pads and there are times I use clothes, it depends on whether my mum has money,” she explained.

Highlighting her family’s economic situation, Obiegwe said, “We will prioritise feeding in the house over me using sanitary pads.”

Prices of sanitary products range from N800 to N2000, with about 8 to 10 pads, or more in some cases. For instance, a Molped Max Thick duo (for heavy flow with 14 pieces) is N2300, a Kotex pad is N950, a Lady Care Premium N800, a Drylove sanitary pad is N900, and a Molped Ultra Soft extra long (for mild flow) is N1400. A Virony pad (with a mix of pads for heavy flow, mild flow and panty liner) is N2000. Thus, for some households, sanitary pads are a luxury.

The same is true for Olufunke* Olanrewaju, a 15-year-old Deaf student, who doesn’t consider purchasing sanitary pads significant compared to other needs. Since she started menstruating in July 2023, she has only been privileged to use sanitary pads a few times after purchasing them on credit.

Olanrewaju, who lives with her petty trader grandmother in Lagos because she could not access inclusive education in her village in Ogun State, found an alternative way to manage her menstruation.

“I use clothes because my aged grandmother cannot afford to buy me pads, as she is a trader (she sells puff puff, soft drinks, and sachet water). My dad is unemployed, and my mum is a trader. Whenever I call my parents for money, it is for something substantial and not for sanitary pads.”

Corroborating Olanrewaju, her mother, Ms Esther Olanrewaju, said, “There are times she would call me to request money for a pad, and I won’t be able to afford it. Sometimes, she asked my mother or my siblings because they all live together in Lagos.

“The truth is, it is not convenient to buy pads for her menstruation all the time. So, there are times she uses pads, and there are times she uses clothes or tissues,” she added.

When asked if she would prioritise sanitary products over feeding, Ms Olanrewaju remarked, “We need to eat first so we can survive; every other thing comes after that.”

Health implications of unhygienic alternative products

Research shows that poor menstrual hygiene leads to harmful effects on a woman’s sexual and reproductive health – including risks for reproductive and urinary tract infections, which can result in infertility and birth complications.

Elizabeth Talatu Williams, Sexual Reproductive Health Advocate, explained that “there are different health implications of using unhealthy sanitary products, such as urinary tract infection or fungi infection.”

Kabirat* Shittu, a 15-year-old Deaf student of Sango Junior Secondary, cannot forget her experience with infection months after it happened. Her single mother, who works as a caterer, struggled to pay her medical bills when Shittu landed in the hospital because of the infection.

Narrating her experience, she said, “I observed that I started having painful menstruation, and in that month, the pain became unbearable. I had a lot of blood coming out of me. I was helpless and weak, so my mum had to clean me up. The menstrual flow continued for days, eventually, my mum took me to the hospital where it was confirmed that I had an infection.”

Shittu was advised to always use sanitary pads along with the prescribed medications, but her family’s economic situation is challenging.

“Despite being told to use pads only for menstruation, I use tissue whenever I am at home so that I can change regularly, but whenever I am going out or in school, I try to use pads. This is also dependent on whether there is money to buy the pad. I wish I could always have access to pads. I don’t want to relive that experience. I don’t want the infection to reoccur,” Shittu added.

Shittu’s mother, who shared that Kabirat had always used tissue for her menstruation before the infection, explained that she has been trying her best to always make sanitary pads available to Kabirat.

“She doesn’t have a specific product of pad that she uses, so I try to purchase the pads for her as I can afford it.”

Ms Shittu expressed her desire to get support for her daughter’s monthly sanitary products, but she is a single mother with many needs to cater to.

“I don’t mind getting support for her to get sanitary pads monthly. She still complains of menstrual pain, and it won’t be good if she has an infection again, all because I can’t afford to purchase sanitary pads for her regularly.”

Lack of WASH facilities in schools worsens the situation

Lack of appropriate facilities such as gender-segregated improved toilet facilities, adequate safe water supply in schools for washing hands and soiled clothes, facility for drying of clothes, and absence of sanitary menstrual materials can prevent girls from safe, hygienic management of their menstruation.

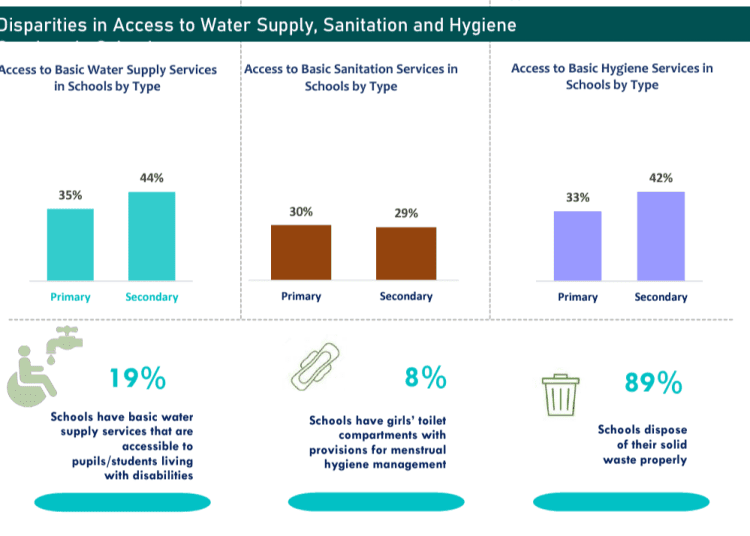

According to the Water Sanitation and Hygiene National Outcome Routine Mapping 2021 (WASHNORM) by UNICEF, about a third of all schools (37%) in Nigeria have basic water supply services, while 30% of schools have access to basic sanitation services. Only 8% of schools have girls’ toilet compartments with provisions for menstrual hygiene management. Handwashing facilities are not available in 49% of schools, while about three in ten schools (35 %) have access to basic hygiene services.

Also, the Sanitation Economy and Menstrual Hygiene Marketplace Assessment, Nigeria, 2022, recorded that only 3.4% of schools have improved toilets/latrines, with separate blocks for males and females, while only 8% of schools have compartments with provisions for menstrual hygiene management. Meanwhile, 81.4% of women have reported having a private place to wash and change at home.

Depending on the menstrual flow, it has been recommended that sanitary pads be changed at least every few hours. Some studies recommend 4 hours, while others recommend 4-6 hours.

The World Bank’s brief on menstrual health and hygiene also noted that girls must properly wash their hands after changing sanitary products because “neglecting to wash hands after changing menstrual products can spread infections, such as hepatitis B and thrush.”

As such, sanitary pads must be changed within school hours, and when there are insufficient Water and Sanitation Hygiene (WASH) facilities in the school, it becomes tedious for girls to maintain a high level of hygiene during their menstrual cycle.

Abigail* Terhemba, a Blind student at Queens College, Yaba, who has always used pads, described her experience of being stained in public as embarrassing.

“I didn’t remember my menstruation was to start that day, and I went to school. I sat down and noticed that I was stained. I had to borrow a pad from someone who had it in class. I felt very bad about the incident because being stained in public is so embarrassing.”

Immediately, Terhemba went to the toilet to clean up. But “the school toilet is not always comfortable and conducive to use. As a blind person with mobility challenges, I need a comfortable place to change my sanitary pads, but I’m usually worried whenever I’m menstruating and in school,” she said.

While Precious* Ogunbiyi, a 17-year-old JSS3 student at Queens College, may share Terhenmba’s feelings of embarrassment about being publicly stained, her experience with the school toilet appears to be different.

“There was a day we had a programme in school, and while we were at it, someone came to inform me that I was stained. I felt somehow, but people were shouting at me. I believe they didn’t understand. Sometimes, I would have forgotten and would be stained. It could also be about the placement of my pad, but I am not sure why. Despite my visual impairment, I try my best to place the pad very well, but I still get stained,” she narrated.

Precious, who is visually impaired, said she imagined what other girls without access to pads go through because “even with pads, I still get stained in school till now because I have a heavy flow.”

Precious, however, remarked that the toilet facilities within the school were comfortable for her to use whenever she needed them.

For Mutiyat* Hamsat, a 20-year-old lady with intellectual disability in Amosun Primary School, Inclusive Agege, her mild menstrual flow makes her unbothered about the need to use the toilet facilities within the school to change.

“The clothes I use from home last me until we finish school. We also do not close late, so I don’t have to bother about changing,” she added.

At Sango Junior Secondary School, there are toilet facilities with running water, which provides comfort for the students whenever they need to use them.

Implication of lack of access to sanitary pads on student’s performance

According to UNICEF’s Nigeria Education Fact sheet (2024), girls make up the majority of the children who are out of school at the junior or senior secondary level. At all levels, the vast majority of out-of-school children reside in rural areas and children from the poorest wealth quintile comprise 51 per cent of out-of-school children of primary school age and 48 per cent of junior secondary school age.

Like Ejiofor, many girls with disabilities are forced to take days off from school during menstruation due to a lack of access to sanitary products and adequate WASH facilities. They often choose to stay home to avoid the embarrassment of staining their clothes at school.

Similarly, Obiegwe missed several weeks of school while recovering from an infection caused by inadequate access to hygienic sanitary products.

Victoria Uzonma, a Legal and Programme Officer at Human Development Initiative (HDI), shared that her organisation’s routine visits to special schools across Lagos state witnessed a decline in the attendance of some schoolgirls with disabilities at specific times of the month.

Victoria explained, “When we asked them, we realised that some of these girls stay at home while menstruating because of the fear of getting stained. Some of them use tissue, rags, and even leaves because they cannot afford to buy sanitary pads.

“In some cases, some mothers would want their children to stay at home so they can adequately care for them, especially those with intellectual disability, and considering that there are no caregivers within their schools.”

Victoria noted that staying away from school while menstruating would affect the girls’ academics, especially because lessons continue whether or not they were in school.

UNICEF also reports that girls’ inability to manage their menstrual hygiene in schools results in school absenteeism, which, in turn, has severe economic costs on their lives and country.

Accessing Sanitary Products in Schools

According to Terhemba, the only time she received sanitary pads in her almost three years of attending Queen’s College was when ‘Old Girls of Queens College’ distributed pads to the students in 2022.

Luckily for her, she always had her sanitary pads from the house before she resumed school, and those were sufficient for her throughout the school term.

Obiegwe, however, has never received pads at school. She recalled an instance of pad distribution where she did not receive any because the pads were insufficient to cover all the students.

Tumininu* Olaniran, a 24-year-old with autism spectrum, has never received a free pad in her over 12 years of menstruating.

13-year-old Busola* Moses, with intellectual and learning disorder, has benefitted from a pad distribution by a Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) at her school. However, she has only received them once since she started menstruating two years ago.

Senior Students, Caregivers, and Teachers providing support

Ogunbiyi, who attended Pacelli School for the Blind and Partially Sighted (boarding primary school), started her menstruation while in school, and she was left to the support of other senior students to guide her.

“I started my period in September 2018 when I was 11 and in Primary 4. School had just resumed on Friday, and my period started the next day. I had no idea my menstruation was going to start, and I was unprepared,” she narrated.

Ogunbiyi, who shared that the Reverend Sisters in the school had sensitised her and other schoolgirls about menstruation, had been looking forward to her period but didn’t realize that it would come with cramps and additional responsibilities of maintaining a high level of hygiene.

Describing her first experience and how naïve she was, Ogunbiyi said, “Some of my friends who started menstruating before me and some senior students who had the experience showed me how to use the pad. Luckily, I had pads because the Reverend Sisters encouraged us to pack pads with our items whenever we were coming to school.”

For some of the Deaf students in Sango Junior Secondary School, communicating their menstrual hygiene needs to their Physical Health Education (PHE) teacher can be difficult, especially when sign language interpreters are not available.

To address this, the sign language interpreters within the school sensitized other teachers about sexual and reproductive health, menstrual hygiene, and basic sign language to enable them to understand the students’ needs.

Ms Seyi-Ojo Ayobami, a sign-language interpreter within the school, said the PHE teacher provides sanitary pads to the girls whenever they are available.

“We have a teacher who provides sanitary pads. She is in charge of the sick bay. She gives them pads if they meet her. If the teacher is not around or there are no pads, they meet other teachers for pads, which in some cases might be positive or otherwise.”

The case is, however, different at Amosun Primary School, Inclusive.

Narrating a recent happening within her school, Ms Akinola, a class teacher and sign language interpreter at the school, narrated the story of a 12-year-old autistic student who saw her period for the first time.

“We observed it because we saw that she was stained. We called the caregiver to clean her up and gave her a tissue to use. She was crying and feeling sad. We eventually called her mother to pick her up. She feels embarrassed, and that’s why she’s not in school today. The situation might have been different if there were pads available to give her,” she said.

Government and other stakeholders’ efforts

Target 2 of the Sustainable Development Goal 6 seeks access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and ends open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations.

In 2024, the Lagos State Government, through the Ministries of Health and Women and Poverty Alleviation (WAPA), and in collaboration with NGOs, distributed 26,000 sanitary products to female students and women across local communities in the state to mark the 2024 Menstrual Hygiene Day.

However, there were no specific indications as to the breakdown of beneficiaries or whether schoolgirls with disabilities were recipients.

Adenike Oyetunde-Lawal, the General Manager of the Lagos State Office for Disability Affairs (LASODA), spoke with BONews and said that “the agency is not distributing sanitary products in this 12-month calendar period, as it is not budgetarily provided for 2024.”

Oyetunde-Lawal also acknowledged that “non-profits, individuals, as well as the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Education have pushed the cause” to enhance access to sanitary products among girls with disabilities.

When asked if this is an area of interest that the agency would like to prioritise in the next calendar year or rather collaborate with other MDAs to ensure that GWDs are also beneficiaries of these initiatives, she remarked, “as with many other causes…yes.”

Making a Case for Collective Intervention

Teachers and caregivers at the Inclusive schools shared concerns that they have heard a lot about pad distributions in the media but have never directly benefitted from them.

Ms Akinola appealed to relevant stakeholders to facilitate the distribution of sanitary products to the schoolgirls.

Akinola, who said it is often perceived that primary school girls do not need sanitary pads, stressed that girls with disabilities access education at different points, and some of them are already mature and have attained puberty despite being in primary school.

She said, “If they can bring pads here, it would be good. Special children are mature already—some start their menstruation by 10 years old, and we have girls that are up to 16 and above here. If we can get a monthly supply of sanitary pads, it would be good.”

According to Ms Seyi-Ojo, some parents cannot afford to provide transportation fare to their children, and such parents would not prioritise sanitary products for their children.

She stressed the need for collective actions from all stakeholders to facilitate the distribution of pads to these girls.

“I have been in this school for about two years, and there has been no distribution of pads. If we can have organisations that can help to give pads to schoolgirls, even if it is twice a year, it will go a long way.”

Uzoma of HDI also proposed a tax rebate and/or subsidy for sanitary products to make it affordable for indigent girls.

“Women menstruate every month, and we all have different flows. Imagine someone with heavy flow having to purchase three packs of sanitary pads in a month; the cheapest pad is about N500, but how many people can afford that?” she queried.

“Even the privileged ones are complaining, how much more indigent girls with disabilities,” Ms Uzoma added.

She also charged NGOs to continue their advocacy to ensure that governments consider menstrual hygiene as a germane issue that should be addressed.

Noting that menstruation is a public health issue that governments must address to protect the education and overall well-being of schoolgirls with disabilities, Sola Abe, a Sexual Reproductive Health Education Advocate, calls for the adoption of gender-responsive education budgeting.

According to Abe, gender-responsive education budgeting is an approach that considers the experiences and needs of boys and girls in budget allocation and spending to ensure access to education, retention in school, and completion of their education.

Abe explained that “one of the key elements of the gender-responsive education budgeting is the provision of sanitary products in schools, and if we are serious about making girls stay in school, we must provide sanitary products for them, considering that most girls cannot afford pads of their choice due to the cost.”

She also emphasised the importance of including menstrual hygiene products in social welfare programmes, ensuring sanitary pads are distributed to poor and vulnerable households during welfare and outreach efforts.

Talatu Williams called for a multi-sectoral approach in which all stakeholders “work together to ensure that sanitary pads are either free or subsidized so that girls can afford them.”

She also called for governments to support CSOs that are producing reusable sanitary pads in large quantities so they can distribute them to schoolgirls, especially in rural communities and informal settlements, who are unable to purchase sanitary products.

Editor’s note: GWDs access education at different stages, and depending on the type of disability, could also impact their learning. Hence, the reason there were ladies in a primary school. Also, names with asterisks are fictitious to protect the identity of the respondents.