Refusing Patriarchal Norms: Why Women Should Keep Their Surname After Marriage & Doing Otherwise Isn’t Feminist

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

As feminism continues to evolve and shape the way we think about gender, identity, and equality, one tradition has sparked intense debate: the practice of women taking their husband’s surname after marriage. This article will explore why choosing to bear your husband’s surname after marriage isn’t feminist.

The tradition of women taking their husband’s surname dates back to medieval Europe, where women were seen as something to be owned and passed from father to husband. This tradition, known as coverture, erased women’s identities and reinforced their “subordinate” status. The tradition persists, with many women still taking their husbands’ names without questioning the implications of their decisions.

In Nigeria and the African society at large, women are conditioned, from a young age, to aspire to marriage. This conditioning, which leads women to believe that they are property, ensures the continuity of the ingrained tradition for women to give up their maiden name and assume their husband’s surname after marriage. Although it is viewed as a symbol of unity and commitment, this tradition sustains a patriarchal system that erases women’s identities, reinforces gender inequality, and restricts their autonomy.

Colonialism and the imposition of Western values on Nigerian culture brought about the emergence of surname change. The British, in particular, introduced the practice of patronymy, where a woman’s identity was tied to her father’s or husband’s name. This system upheld the belief that women were an addition or an attachment to men instead of being independent individuals with their own agency.

However, feminists endeavour to challenge and dismantle patriarchal systems that enforce gender inequality. As such, one subtle but significant way to challenge the system is not taking a man’s surname after marriage, which is a patriarchal concept.

This is because the practice of surname change is rooted in the patriarchal belief that men are dominant and women are subordinate or that men are superior to women. This belief continues to reinforce the idea that men are the head while women are the tails, neck, or spinal cord and that a woman’s identity is inextricably linked to her relationship with a man rather than her own individuality. A woman’s identity and autonomy are lost to her husband the minute she takes on his name.

When a woman changes her surname, she erases her identity and heritage. Her maiden name, which connects to her familial and cultural roots, is replaced by her husband’s name, symbolising her new role as his wife. In contrast, there is no name change on the man’s end to symbolise his role as her husband. This erasure of identity is a stark reminder of the patriarchal belief that a woman’s value lies in her relationship with a man rather than her inherent worth.

The practice of surname change also restricts women’s ability to exist for themselves. A woman who takes her husband’s name may feel pressure to conform to societal expectations of a “good wife” rather than forging her own path. This often leads to losing personal freedom and independence, as she becomes defined solely by her relationship with her husband.

This patriarchal norm extends to children, who often bear only their father’s name. This enforces that children are their father’s property rather than individuals with identities and agency, just like their mothers. As such, women refusing to change their surnames challenge the notion and assertion of women’s identity and autonomy as mothers.

Some argue that taking a husband’s surname is a personal choice that shouldn’t be judged or politicised. However, this perspective overlooks the broader social implications of this tradition. In a patriarchal society, personal choices are often shaped by systemic inequalities and cultural norms. A personal choice like that can reinforce harmful gender stereotypes and contribute to a broader culture of discrimination and marginalisation.

Not all Nigerian women conform to this tradition. Some choose to retain their maiden name, hyphenate, or adopt a new surname. These women are challenging the patriarchal norms that have governed Nigerian society for centuries. These alternatives challenge patriarchal norms, assert women’s autonomy and agency, and is quite fair.

Also, a woman choosing to bear her husband’s surname isn’t feminist because it perpetuates patriarchal oppression, erases women’s identities, and restricts their autonomy. While personal choices are important, they must be considered within the broader social context. By challenging this cursed tradition and exploring alternative naming practices, we can work towards a more equitable society where women’s identities and agency are valued and respected.

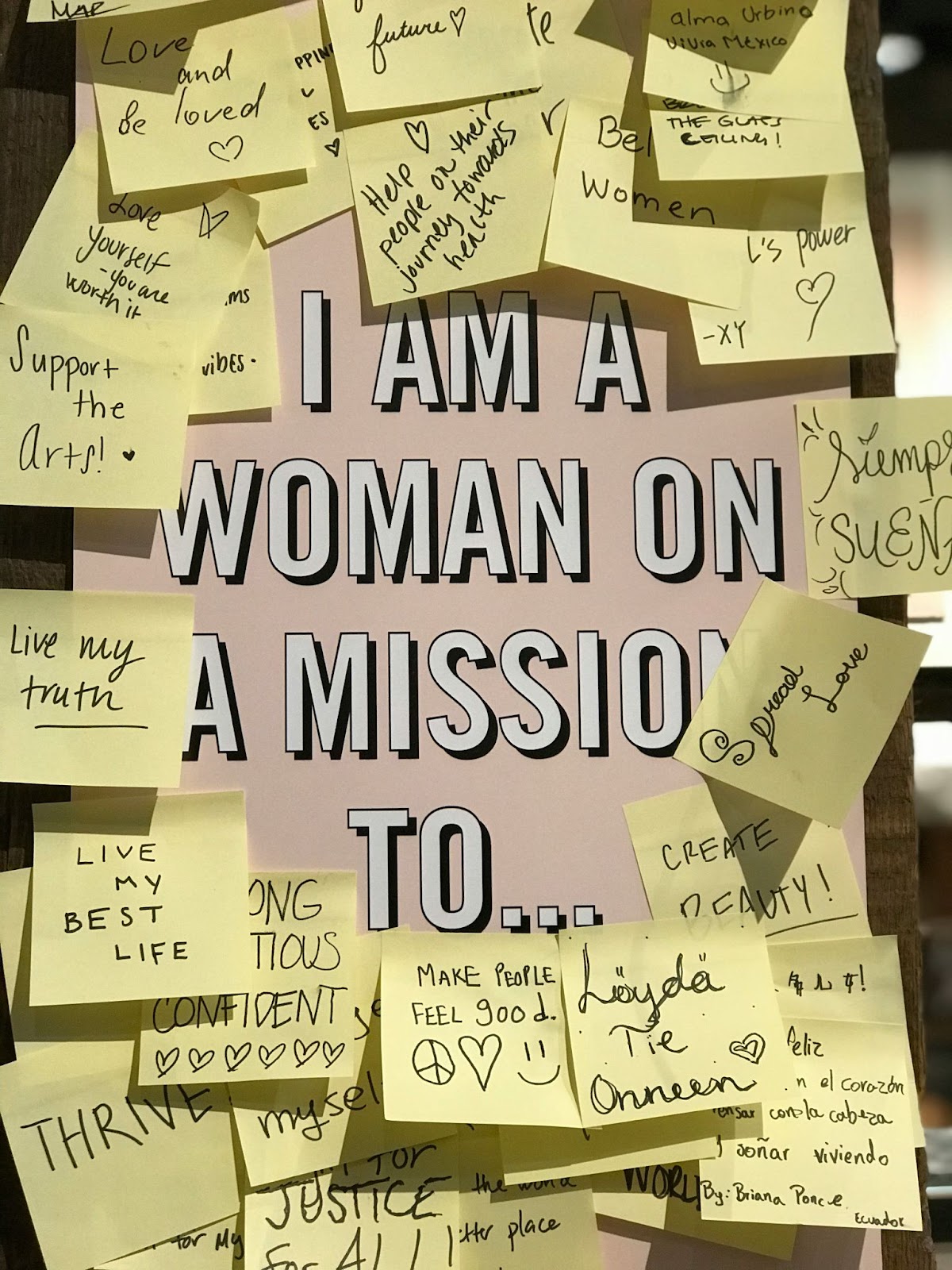

Women refusing to change their surname to their husbands after marriage is not just a personal choice; it’s a political statement, a crucial act of feminist resistance. It’s a declaration that women will not conform to patriarchal norms and ideologies that aim to erase their identities and continually reinforce gender inequality. It’s a commitment to challenging the status quo and creating a more equitable society.

As such, it is paramount that women embrace this act of defiance and forge their paths rather than conform to harmful gender stereotypes. By doing so, we can work towards a more equitable society where women are valued as independent individuals rather than mere accessories to men.