|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

In Nigeria, the history of women’s education is a tale of resilience, advocacy, and gradual change. Over the years, cultural, religious, and socio-economic factors have influenced the access women have had to education. From pre-colonial times through colonial influence and into the post-independence era, women have faced numerous barriers. Despite this, efforts toward empowering women through education have persisted, with significant progress made, though challenges remain.

Recently, there has been a debate on X (formerly Twitter) about whether women’s right to education is connected to feminism. Some argue that the push for women’s education isn’t solely tied to feminist movements, questioning the idea of framing it within gender equality. Despite this debate, it’s clear that the fight for women’s education in Nigeria has always been about empowerment and equality beyond any specific ideology.

Across Nigeria, regional differences in female education access persist. Northern states such as Kano, Sokoto, and Zamfara face cultural and religious challenges that hinder women’s participation in education and politics. In the Northeast and Northwest regions, child marriage and insurgencies like Boko Haram have severely impacted girls’ ability to attend school. In the southern regions, while the situation may differ, issues such as legal protections against violence, reproductive health rights, inheritance rights and limited employment opportunities for women still exist.

Before the advent of formal education systems, Nigeria had its own indigenous education, which focused on the transmission of skills needed for societal roles. Women’s education typically involved domestic training, agriculture, and crafts, such as weaving and pottery. In some communities, particularly among the Yoruba and Igbo, women played significant roles in commerce, necessitating a form of informal education that included numeracy and communication skills.

The introduction of Western education by missionaries in the 19th century marked a pivotal change. Mission schools were initially focused on educating boys, which was in line with the belief that men were to become breadwinners and leaders. As a result, women’s roles were confined to the home, and early mission schools often offered girls a curriculum focused on domesticity and basic literacy. Despite this, a few mission schools began to accept girls, signalling the beginning of women’s involvement in formal education.

Before 1920, primary and secondary education in Nigeria was largely controlled by voluntary Christian organisations. Of the 25 secondary schools established by 1920, only three were for girls, with the rest being for boys. In 1920, the colonial government began granting funds to these organisations, a practice that continued until the early 1950s. By 1949, out of 57 secondary schools, only eight were exclusively for girls. Notable girls’ schools included Methodist Girls’ High School (1879), St. Anne’s School, Molete (1896), and Queen’s College, Lagos (1927). By 1960, the number of girls’ schools had increased to fourteen, while boys’ schools numbered sixty-one, with ten mixed-gender schools.

After Nigeria’s independence in 1960, the government launched the Universal Primary Education (UPE) program in 1976, aiming to provide free and compulsory education for all children. While this was a step forward, girls in some regions, especially in northern Nigeria, still faced significant barriers, such as early marriage and religious customs that restricted access to education.

Despite the many campaigns for educational reforms since 1925, patriarchy, religion, traditional customs, and socio-cultural barriers continue to limit women’s educational opportunities. Research from the Journal of Women Empowerment and Studies has shown that women, particularly in rural areas, face challenges such as cultural practices, societal expectations, and early marriage, which hinder their education. Additionally, limited access to schools, parental resistance, and poverty are persistent barriers.

Nigeria’s commitment to women’s education has evolved through legal reforms, starting with the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) in 1948. In 2003, the Child Rights Act was enacted, emphasising free and compulsory education for both girls and boys. Feminist organisations, such as Women’s Rights Advancement and Protection Alternative (WRAPA) and BAOBAB for Women’s Human Rights, played key roles in advocating for legislative changes that prioritise gender equality in education.

Over the years, notable Nigerian figures have advocated for women’s rights, particularly in education. Chief Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti was a pioneering figure known for her activism and efforts in establishing literacy programs for women. Lady Kofoworola Ademola and Hajia Gambo Sawaba also played critical roles in promoting education for girls, advocating for women’s rights, and challenging traditional societal norms. The rise of women leaders like Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala and Amina Mohammed has helped promote the importance of education for women, both locally and globally. These women have not only advocated for educational reforms but have also demonstrated the power of education in achieving gender equality.

Feminist movements have been instrumental in advocating for education as a fundamental right for girls. Organisations like the Malala Fund and Education as a Vaccine (EVA) have been working to increase access to education, particularly in Northern Nigeria. These efforts also address gender-based violence in schools and encourage girls to pursue fields traditionally dominated by men, such as STEM.

Despite the challenges that remain, the history of women’s education in Nigeria shows that progress is possible when there is collective action. Advocates and feminist movements have been at the forefront of this battle, pushing for policy reforms and a cultural shift toward greater gender equality.

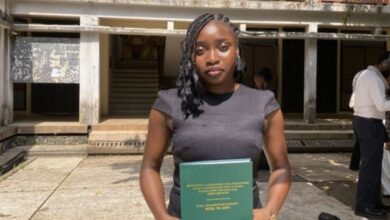

Feminists on platforms like Twitter, such as Ene, have actively worked to keep girls in school, while Ruby Lauren has created scholarship opportunities for women in tech. These efforts continue to support and advance the education of girls in Nigeria. By continuing to champion women’s educational rights, Nigeria can unlock the potential of millions of women, contributing to a more inclusive and prosperous society.