Osinachi Nwachukwu’s voice filled churches across Nigeria. Congregations swayed to “Ekwueme,” her collaboration that became a worship anthem. On stage, she radiated joy, faith, and power. Behind closed doors, her husband kicked her in the chest.

She died in April 2022.

Initial reports claimed throat cancer. Then the testimonies began—from family, church members, neighbours.

As reported by Premium Times, Ms Caroline Madu, mother to the late singer, informed the court, “Peter called me a witch, sent me out of his house, and it was a man from Delta State that accommodated me. I saw her last December when she came to Enugu for a programme. Before then, there was a time she left her matrimonial home because of the ill-treatment, and she stayed with me for a year and three months before Peter came with a pastor to beg as he had turned a new leaf.”

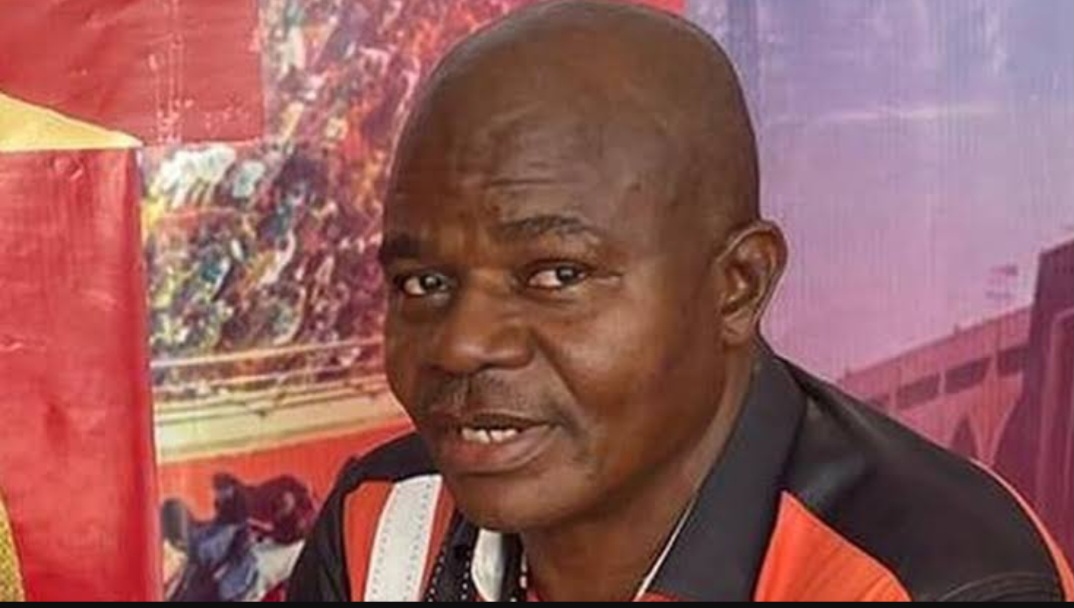

They revealed a pattern of domestic violence so severe that Nigeria’s Office of the Attorney-General charged her husband, Peter Nwachukwu, with 23 counts, including culpable homicide, criminal intimidation, cruelty to children, and spousal battery. In a packed courtroom, 17 witnesses testified, including Osinachi’s own two children. Twenty-five documents were submitted as evidence.

On a Monday in 2024, Justice Nwosu-Iheme of the High Court of the Federal Capital Territory delivered the verdict: Guilty. Peter Nwachukwu was sentenced to death by hanging.

But the question that haunts Nigeria’s faith communities remains: How did a beloved gospel singer, surrounded by church family, end up dead at her husband’s hands? And how many other women are singing on Sundays while suffering in silence?

The Theology That Traps

For women in certain African Christian spaces, the answer is embedded in what’s preached from the pulpit every week: absolute, unilateral submission of wives to husbands—no questions asked.

Gender advocate Busola Rafiat Ojo-oba, founder of Teachers Against Abuse, identifies the fundamental problem:

“Religion teaches submission to a man/husband as the head of this house, and in more ways than one, this encourages domestic violence/abuse towards women. Instances like ‘women should not be seen/speak in public’ also contribute to the erasure of women and girls in public spaces.”

On a woman’s digital community, when asked how Christian marriages talk about submission, a woman named Favour wrote, “They talk about it exactly as the Bible says. Submit to the man. No questions asked. Just submit. It’s in plain English, not much to misinterpret there.”

Ann, founder of the community, has witnessed how this doctrine devastates women: “I have seen submission and sexual purity used to justify all sorts. From rape. To domestic abuse. To encourage women to shrink. I’ve seen a woman made to kneel and thank her husband in the presence of the whole church. I’ve seen unmarried women treated like eyesores. I’ve seen women lose their sense of conviction and strong will just by becoming more religious.”

This theology, women as inherently lesser, submission as absolute, doesn’t just wound. It creates conditions where abuse flourishes unchecked, where leaving becomes unthinkable, where violence escalates until it’s fatal.

When Femicide Becomes the Final Chapter

“Femicide is the killing of women because they are women. It is the final stage of unchecked domestic abuse,” explains Ololade Ajayi, gender advocate and founder of DOHS Cares Foundation. “In fact, one of the parameters to determine if a killing is femicide is a history of domestic abuse. The abuser’s response to the woman leaving or seeking help might be fatal, leading to the death of the woman, and that is femicide.”

The statistics are staggering. In 2023 alone, Africa recorded the highest rate of intimate partner and family-related femicides in the world, with 21,700 women losing their lives. In Nigeria, “there are many laws that address IPV, but none recognise Femicide,” Ololade notes. “There should be specific laws for femicide that distinguish it from homicide that takes into account a prior history of domestic violence, of what distinguishes femicide from homicide, gender gender-related motive.”

So far in 2025, DOHS Femicide Observatory, Nigeria’s first, has recorded 104 reported cases and 119 deaths.

These aren’t just numbers. Each represents a woman who might have been taught, like Osinachi, that submission was her spiritual duty. That leaving was disobedience. That suffering was sanctification.

When Churches Become Accomplices

The role of religious institutions in enabling abuse emerges clearly in survivor accounts and family testimonies. When asked if she has encountered survivors who said church teachings or religious beliefs made it difficult to leave an abusive relationship, Ololade responds carefully: “So they don’t actually outrightly say that church told them not to go. But what happens is that you will report these cases to churches and then these churches call them and settle it by encouraging them to keep praying.”

She cites a recent case: “Barrister Temitope Odu, who died in Ikorodu, Lagos. The family allege that the pastor was the one settling cases for them and encouraged her stay. But the church backtracked when she died and said they told her to leave.”

Busola expands on this pattern of institutional complicity: “Religion perpetuates violence because of the culture of submission that they preach, enforcing hierarchy, gender roles. And because of victim-blaming, there is nothing a woman does that will ever be acceptable or enough. She will be blamed for even getting abused, because we have a culture that covers up for abusers. The church and mosques are very complicit in the face of violence.”

The contradiction is cruel: churches counsel women to stay, to pray, to submit, then express shock when those women die. Busola notes: “But when these women die, then they start saying Why didn’t she leave? But all through the abuse, you all didn’t create a safe space for her nor reprimand the abuser, so how would she have left? No safety, no safe harbour, no nothing.”

This pattern, women trapped by theology, churches prioritising marriage over safety, and pastors “settling” abuse cases behind closed doors, creates a deadly ecosystem. Osinachi’s case suggests that even public figures, women whose voices reached millions, couldn’t escape it. The testimonies from her family, church members, and neighbours paint a picture of violence known but not confronted, suffering witnessed but not stopped.

The theological framework enables this silence. When submission is presented as non-negotiable, when questioning a husband’s authority is equated with disobeying God, and when church leaders counsel prayer instead of safety, abuse doesn’t just continue. It intensifies.

In Kenya as well, gender based violence is rife, and this is despite the country being “80% Christian.” Emily Onyango, the first female Anglican bishop in Kenya and chair of African Church For Biblical Equality, in a lecture titled “The Challenge of Gender Based Violence in Kenya and the Response of the Church” from the 2016 CBE International Conference “Truth Be Told” in Johannesburg, South Africa, identifies the core issue:

“The major factor is patriarchy. That is male power or male domination. And male power or male domination is mainly created through improper understanding of the African culture and the Bible.”

She cited texts like Ephesians 5 and Proverbs that have been weaponised to the point where women submit to their death. Her response to stop Gender Based Violence is to ensure “the church must stand for the gospel of Christ and interpret the Bible in a way that people learn equity.”

Her organisation has developed a training manual for clergy and church leaders on how to interpret scriptures correctly to promote gender equality.

A Call for Accountability

What, then, must change?

Busola is unequivocal about what religious institutions must do: “Religious leaders should enforce strict sanctions such as ostracising male members that perpetuate abuse of the women in the congregation. Also, cases of abuse/femicide should be treated as a crime instead of calling it marital problems.”

Ololade Ajayi echoes this call for institutional accountability, insisting that advocacy groups, churches, and faith-based organisations must collaborate more effectively to protect women and prevent femicide.

“All these undertones of submission, of women’s roles, are part of what contributes to violence and femicide at the end of the day. They should also preach on the pulpits that women’s rights are not to be subjugated. That they do not own them because they married them.”

The call isn’t for churches to abandon Scripture but to stop distorting it. To recognise that teachings on submission have been corrupted by patriarchy and wielded as weapons against women. To acknowledge that when doctrine is used to justify abuse, trap women in violence, and silence their cries for help, it has ceased to be biblical and has become blasphemous.

Osinachi Nwachukwu’s voice, which once lifted thousands in worship, was silenced by the very theology that should have protected her dignity. Her death, and the deaths of thousands of women like her across Africa, demand more than mourning. They demand accountability. They demand reform. They demand that churches stop preaching submission that kills.

The verdict in Peter Nwachukwu’s trial was clear: Guilty—death by hanging.

But what verdict will Nigeria’s churches render on their own complicity? What sentence will they impose on theology that enables violence, normalises control, and turns silence into a spiritual virtue?

Until churches confront how their teachings contribute to femicide, Osinachi’s death will not be the last. And every woman singing on Sunday while suffering in silence will wonder: Am I next?