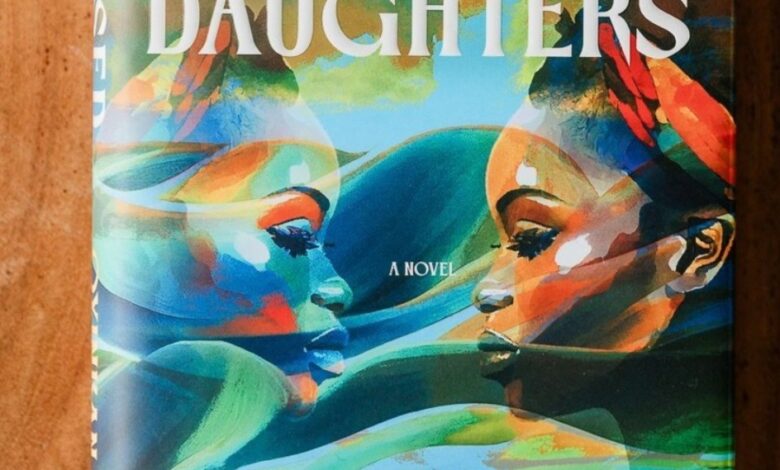

The Myth of Curse: How Men’s Infidelity Became Women’s Destiny Through Oyinkan Braithwaite’s The Cursed Daughters—

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Summary: The Cursed Daughters by Oyinkan Braithwaite’s novel centers on the Falodun women, who are bound by a long-standing family curse. This curse has resulted in generations of abandoned women living together in a large, dilapidated house in Lagos, Nigeria.

Whenever feminism is mentioned, it’s often reduced to conversations about patriarchy, equality, women’s rights, and autonomy. While these remain central to feminism, an attention to women’s inheritance, silence, and intimate harsh realities reveals something deeper. In this sense, feminism is also about matrilineage – the passing down of silence, survival, pain, and memory from one woman to another. This is why “ The Cursed Daughters” by Oyinkan Braithwaite can be read as a feminist novel.

Through the multigenerational women of the Falodun family, Oyinkan Braithwaite explores not only the curse as a generational trauma, but I interpret it as a socialised intergenerational trauma shaped by patriarchal control. In this sense, the curse is a gendered tool used to expose how women inherit suffering in societies that continuously discipline their bodies, choices, and voices. The supposed curse originates with Feranmi Falodun, the family’s mythic ancestress, who enchanted a married man, provoking a confrontation from his wife. Her statement “Your daughters are cursed—they will pursue men, but the men will be like water in their palms.” became the water that continues flowing in the Falodun maternal lineage. But the truth is, the curse is a patriarchal tool that shifts the burden of men’s moral failure onto the women. This is demonstrated in many instances of the novel – characters like Bunmi endure obvious signs of cheating—lipstick stains, perfume, and discarded condoms with dutiful silence. This curse shapes the Falodun’s women’s behaviour, trapping them in unfavourable relationships and cycle of victimhood while the men move on without consequence.

In The Cursed Daughters, the Falodun’s women want to protect their daughters from the curse, but they could only pass pains and sufferings, reframing the curse as a metaphor for everyday women harsh realities. This showed how pain and sufferings are passed from one woman to another, just like how the killing of a woman endangered the lives of others.

While patriarchy might not be loud in Oyinkan’s novel, it’s structural. The men’s presence in the novel is distant and inconsistent yet serve as a determinant for the women’s choices. For instance, Monife, Eniyii’s aunt, drowned herself in the Eleguishi due to Golden Boy’s betrayal. Bunmi remains stuck in a cycle of waiting for her ex-husband to return. All Falodun’s mothers preached to their daughters to welcome men’s betrayal and unfailed marriages. Through this, Oyinkan demonstrated how women frequently carry consequences of choices they were never part of.

Oyinkan’s exploration of the Falodun’s women relationship is central to female solidarity. Readers see matrilineage as a world of women. They create a space where they can exist outside of the male gaze and the family house in Lagos is the physical manifestation of the women’s solidarity. The frequent references to their hairstyles serves as a symbol of cultural identity and a private language shared between Nigerian women.

In the end, the novel’s greatest feminist triumph lies in its refusal to look away from the supposed generational curse that Falodun’s mothers pass to their daughters. It suggests that the true curse is not the absence of a husband, but the presence of a socialized belief that a woman’s life is merely a waiting room for male validation. It reveals how rather a patriarchal defense mechanism is designed to absolve men of their moral failures while shackling women to a legacy of perpetual penance.