Beyond Monuments: Yvonne Adhiambo’s Dust Women’s Narrative

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

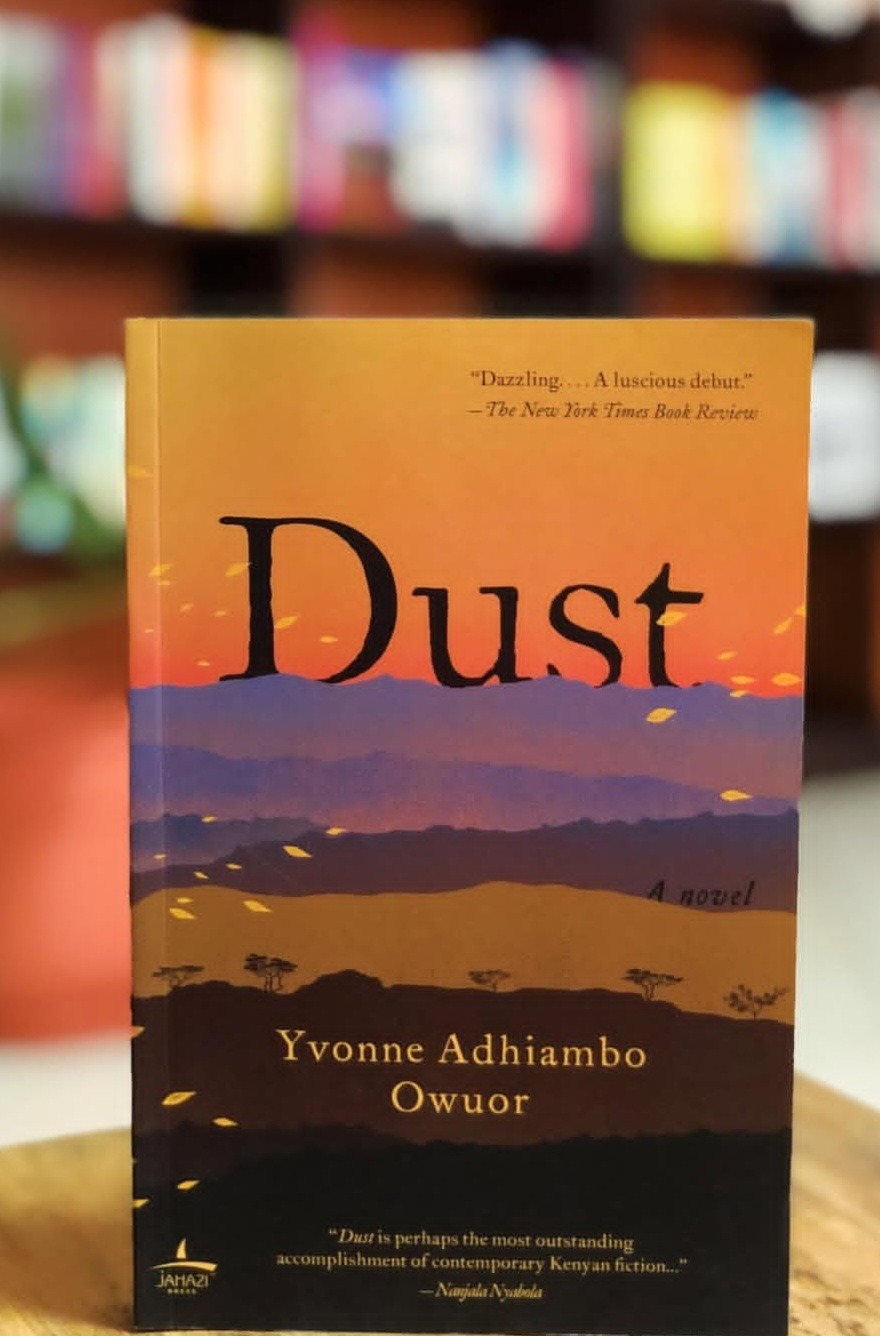

In every historical book, masculine storytelling, political achievements, and monuments dominate. It’s almost as if the women never existed, so their stories and contributions are buried. In Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor’s Dust, the novel challenges the historical masculinist storytelling and official state record that prioritises male leaders and their political achievements.

The novel opens with the death of Odidi Oganda during the 2007to 2008 post-election violence in Nairobi, Kenya. While the state’s historical record focuses on men’s political power and struggles, like the assassinations of Tom Mboya and Robert Ouko, the novel uses these events to highlight how women bear the gendered historical burden of national trauma. She replaces the masculine obsession with power and monuments with a feminine insistence on memory and naming.

Initially living in her brother Odidi’s shadow, Ajany spent seven years in exile and returned to Kenya after his death. She defied the traditional norms of grieving in silence and instead chose to uncover the truth surrounding her brother’s death. Through this, she asserted her power of choice and rejected the collective belief favoured by the men around her. She also acts as a postcolonial detective, utilising her memory and art as forensic tools to dismantle the state’s masculinist storytelling.

As the chief mourner, Akai-ma, Odidi’s mother, rejects the narrative of the national Mother. Her uncontained grief and eventual flight into the desert emphasised her refusal to perform the stoic role typically assigned to women in masculine nationalist projects.

Yvonne’s analysis of a structure built on the Mau Mau rebellion, political assassinations, and the 2007 election violence depicts that the cycle of political violence is fueled by the systematic male toxicity that equates leadership with suppression of the truth. The novel argues that the nation’s violence cannot be settled by male-dominance, but by the feminine act of mourning and naming the perpetrators.

In the end, Ajany reclaims her ancestral land, suggesting a future that is not inherited through male-dominated lineages but through an honest reckoning with the past. She finally extracts confessions from her parents about their traumatic histories, and breaks the cycle of masculinist storytelling through her detective armour. Both Ajany and Akai ultimately utilise physical and emotional flight as a means of maintaining independence in a society that attempts to categorise them solely by their relationship to men.