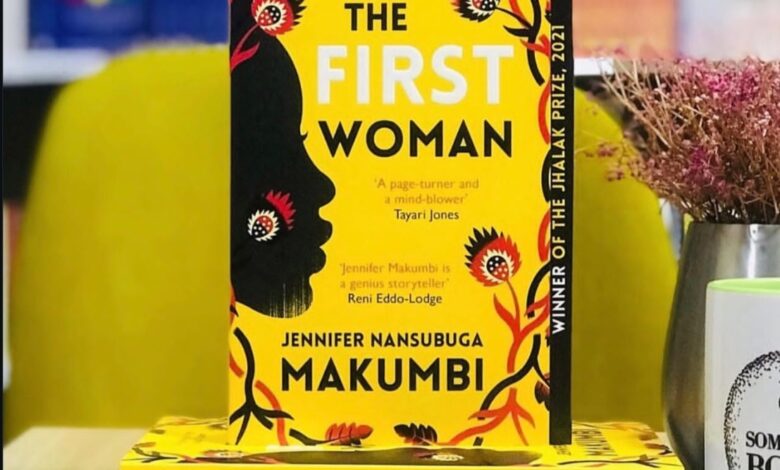

Beyond Western Waves: Discovering African Feminism in The First Woman by Jennifer Nansubuga

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Summary: In The First Woman, Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi illustrates how feminism is not a foreign thing, but a reclaim of the original state of African female power that existed long before colonial and religious suppression. It is a story that returns to a time when women were the architects of kingdoms, the gatekeepers of commerce, and the vessels of human strength.

The origin of African women’s agency and authority did not come from foreign theories of Victorian gender. It emerged from lived experiences of figures like warriors Queens like Amina of Zazzau, the Kandakes of Kush, the economic dominance of West African Iyalodes who controlled vast trade networks, and sacred protests taken to challenge patriarchal policies. In truth, feminism existed in Africa long before white people came.

In The First Woman, Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi illustrates how feminism is not a foreign thing, but a reclaim of the original state of African female power that existed long before colonial and religious suppression. It is a story that returns to a time when women were the architects of kingdoms, the gatekeepers of commerce, and the vessels of human strength.

Summarily, Jennifer tells the coming-of-age story of Kirabo, a headstrong young girl and her quest for identity. Set against the backdrop of 1970s Uganda during Idi Amin’s brutal regime, the author masterfully interweaves Ugandan folklore and history with themes of feminism, belonging, and the power of women. Driven by curiosity and the desire to know her mother and an emerging sense of rebellious nature, Kirabo seeks answers from Nsuuta, a local woman often referred to as a witch, who lives outside the community and shares the history of a feud with Kirabo’s grandmother.

The novel honestly addresses how women sometimes uphold patriarchy by policing one another. This theme is most visible in the way the female characters act as the primary enforcers of the patriarchal status quo. They policed one another’s bodies, voices, and ambitions to ensure communal survival within a rigid social hierarchy. For instance, Kirabo has been subjected to this intergenerational policing from a young age. Her grandmother and aunts demand she squeeze herself into the submissive molds of a proper woman; kneeling, crossing her legs, and silencing her inquisitive nature. This internalisation is so deep that the women even developed derogatory vocabulary for their own anatomy, they referred to their genitalia as “the ruins” or “the burden”. They effectively view their own bodies as sites of shame and liability rather than power.

Rather than paint the perfect picture of mother in every African and Western folklore, Jennifer presents motherhood as a site of complexity, individual agency, and necessary reprieve. At the heart of the novel is Kirabo’s desperate search for her biological mother, Nnakku Lovinca, whose choice to walk away from her child is framed by society as a moral failure and a void in Kirabo’s soul. However, Jennifer dismantles this bad mother title by revealing Nnakku as a woman who chose her own survival and ambition over a marriage that would have erased her identity, thereby validating female agency beyond caregiving. The novel further redefines maternity through the lens of indigenous communal care, where the burden of raising a child is shared among an army of aunts and grandmothers. She even introduces the concept of mothering breaks, moments where women return to their own clans for refreshment away from the domestic grind. Ultimately, she presented the absent mother not as a moral failure, but as a human being with individual agency who refused to be erased by the rigid expectations of the maternal ideal.

In the end, The First Woman is a foundational text for African feminism (mwenkanonkano) that challenges the notion of feminism as a Western import. Through the concept of kweluma, Jennifer suggests how women can become the most vigilant gatekeepers of one another’s ambitions.