Femicide and male violence against women have become a growing and disturbing reality in Borno State, where years of armed conflict, displacement, and weakened community structures have created conditions that endanger women and girls.

Femicide, an intentional killing or severe violation of women by men because of their gender, is becoming an increasingly alarming reality in Borno State. Though many cases go unreported due to fear, stigma, and weak accountability systems, available data and recent incidents reveal a disturbing pattern of violence targeting women and girls.

Borno State has been the centre of Nigeria’s Boko Haram/ISWAP insurgency for more than a decade. The conflict has killed thousands, displaced millions and destroyed livelihoods, leaving many women and girls more exposed to issues like sexual violence, forced marriage and domestic abuse.

The International Organisation for Migration publication report states that among GBV survivors seeking assistance, 44% are children, and 98% of those children are girls, indicating that young girls are disproportionately affected.

A 2024 Amnesty International investigation said, based on 126 interviews, girls in Borno face extreme violence, including rape, forced marriage, sexual slavery and exploitation, not just from insurgent groups, but also from the neglect of families and local structures meant to protect them.

The report describes many girls’ childhoods as stolen twice, first by perpetrators and then by a system that provides little justice or rehabilitation.

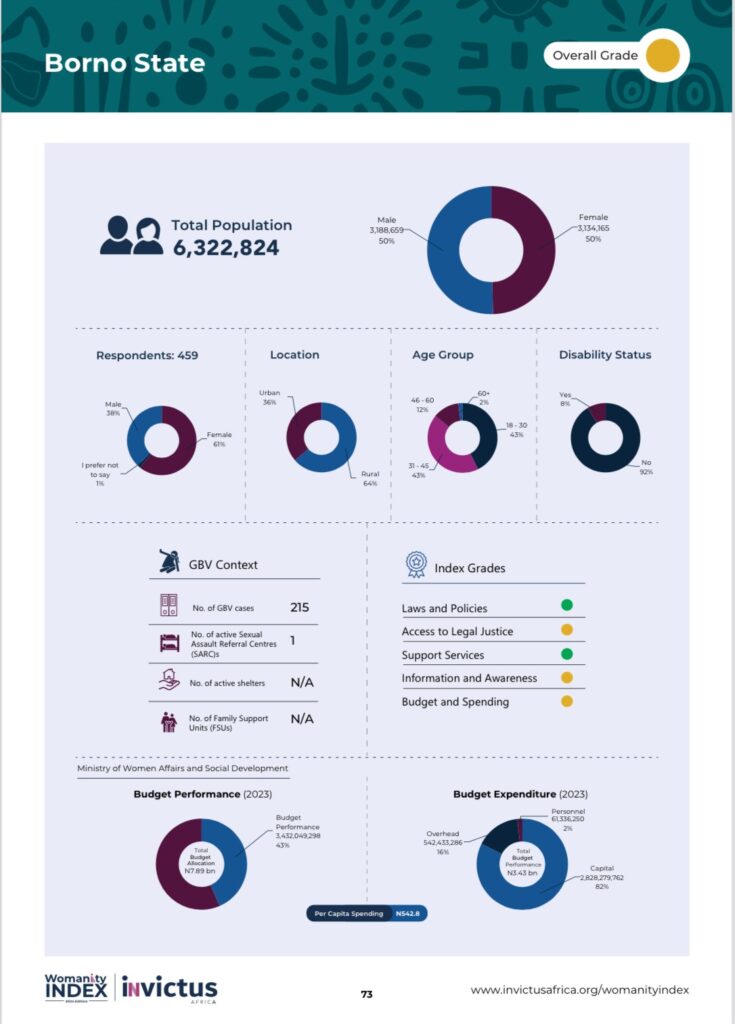

Additionally, a recent Borno-focused brief by InVicTus Africa reported 215 GBV cases in 12 months, with only a fraction resulting in convictions, underscoring significant gaps between the incidence of GBV, reporting, and successful prosecutions.

Recent cases in Maiduguri, including the rape induced pregnancy of a 13-year-old vulnerable girl and the attempted killing of a bride-to-be by her stepmother, have once again exposed how deeply rooted and devastating this silent crisis has become.

Hauwa’s Childhood Stolen by Rape

One of the most heartbreaking cases is that of 13-year-old Hauwa Muhammad, a deaf and mentally ill orphan from the Jajeri community along Baga Road.

Left without parents, Hauwa was passed from relative to relative. Many refused to keep her, calling her “cursed.” Others lacked the patience or resources to care for a child living with disabilities.

Her uncle, Musa Usman, took her in despite financial hardship. But Hauwa often wandered, unaware of danger, and one of those wanderings led to the three-week nightmare that ended in pregnancy.

Hauwa, who became a young mother, still speaks like a child, plays like a child, and dreams like a child until a man who could be three times her age steals her childhood.

She recently became a mother after delivering a baby boy through a Cesarean Section at the Maryam Abatcha Hospital in Maiduguri, months after she was found pregnant following a tragic rape incident.

She had gone missing for nearly a month earlier this year and returned home confused and unable to explain where she had been.

“One day, she left and didn’t return. We searched everywhere for weeks, didn’t know if she was alive or dead,” her cousin Zainab, who spoke for her, said.

A scan later revealed she was pregnant, confirming she had been assaulted during the period she disappeared.

Her godmother, Khadija Ramat, who found her in the midst of children mocking her, located her guardian and helped publicise the issue, which ultimately helped Hauwa get the aid she needed.

“I went to their community for a personal purpose and saw Hauwa surrounded by girls her age, but they were mistreating her,” Khadija said.

“It wasn’t until I came that the situation got the needed attention,” she added.

However, before the delivery, Khadija had been caring for her with the little she had and said both the baby and mother are stable after the birth.

Hauwa’s story illustrates the systemic neglect faced by vulnerable children. It aligns with the National Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS 2021), which found that girls with disabilities are three times more likely to face sexual violence in Nigeria.

A Bride-to-Be Burned and Stabbed by Her Stepmother

While Hauwa’s life changed through sexual violence, another young woman in Maiduguri is now fighting for survival after a brutal domestic attack. Fatima Talba Alkali, who was preparing for her wedding, was attacked by her stepmother just months before the ceremony. Fatima had returned to her father’s house in Jiddari Galtimari to complete marriage formalities when tensions escalated.

Fatima stayed with her mother when she got a marriage proposal, but faced mockery from society during her marriage preparation because she had no father, and she wanted to prove them wrong. Upon reaching her father’s house, after fixing a wedding date, the stepmother had opposed her presence in the house, and reportedly threatened to kill her a day before the incident.

The following morning, she boiled two bottles of groundnut oil and poured the scorching liquid on Fatima’s face before stabbing her repeatedly with a knife she had prepared beforehand. Fatima’s little stepbrother intervened to stop the attack. Her father, Talba Alkali, a retired civil servant, said he had tried to prevent the conflict and had even reported the stepmother’s earlier threats, but the violence still happened.

“I warned her many times never to harm my child and even reported her threats. But I never imagined this,” he said.

These two incidents mirror what many organisations describe as a silent but worsening pattern. A 2023 UNFPA report noted that one in three women in Borno has experienced violence, ranging from sexual assault to extreme domestic abuse. Reports also revealed that poor economic conditions, trauma caused by years of insurgency, and weakening family systems are also contributing to the rising cases.

Some survivors do not receive justice due to social pressure to settle matters at home, while perpetrators often escape prosecution or face delayed trials. This culture of silence, combined with the vulnerability created by poverty and displacement, continues to expose women and girls to further danger.

Hauwa and Fatima’s experiences underscore the urgent need for stronger legal action, community awareness, and support systems to protect women and girls. Hauwa, a child who should have been in school or therapy, now has the responsibility of caring for a baby she never chose to conceive, while Fatima, once preparing for her wedding with joy, now faces physical scars, emotional trauma, and financial struggles.

Their pain reflects a broader crisis that continues to claim the futures of many young women in the state. As Borno works toward rebuilding after years of conflict, the protection of women and girls must remain a priority. Hauwa and Fatima’s stories should not just spark temporary outrage; they should push authorities, community leaders, and policymakers to address the root causes of femicide and violence.

These Girls Deserve Futures

Despite the gravity of their ordeals, both Hauwa and Fatima have attracted the attention of the Borno State Ministry of Women Affairs, with Commissioner Hajiya Zuwaira Gambo intervening in their cases.

In Hauwa’s situation, the ministry supported her throughout her pregnancy, ensuring she delivered safely through a Cesarean Section and providing essential supplies for her newborn.

In Fatima’s case, the commissioner has been following developments closely as the police handle the investigation and the survivor receives treatment at the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital. But while these interventions are commendable, they represent only the first steps in restoring the girls’ lives. What Hauwa and Fatima urgently need goes beyond temporary relief; rather, they also need justice, accountability for the perpetrators, and long-term support that empowers them to rebuild their futures.

This means access to education, psychosocial care, and skill building that can help them become independent and secure. Anything less would leave the cycle of violence unbroken and deny them the chance to rise above the tragedies upon them. Hauwa, a child who should be in school and therapy, now nurses a newborn she never chose, and Fatima, once a joyful bride-to-be, now faces months of painful recovery and emotional trauma.

Their lives were brutally altered by violence that could have been prevented. Yet their stories are also a call to action, reminding authorities, policymakers, community leaders, and the public that protecting women and girls is not optional but fundamental to rebuilding Borno after decades of instability.

For Hauwa, Fatima and the countless unnamed victims, the demand is simple: they deserve justice, safety, and the chance to rebuild their lives beyond the violence that tried to break them.

Borno can break the cycle of femicide by better prosecution, stronger community surveillance, mental-health support, enforcement of child rights laws, and ending the culture of silence.