|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Summary: Amid outrage over the Electoral Act amendment, critics of Godswill Akpabio resorted to feminising him to imply incompetence. This article argues that such rhetoric is misogynistic and distracts from real accountability. Nigeria’s political failures stem from male-dominated power structures, underscoring the need for systemic reform and greater women’s representation.

Nigeria’s civic and media space has erupted in outrage over the Senate’s handling of the Electoral Act amendment and electronic transmission of results. Many Nigerians believe the bill is essential to guaranteeing a free and fair election. The bill, which the Senate didn’t approve, has sparked public outcry and peaceful protests across the nation, calling on all lawmakers, especially the Senate President, Senator Godswill Akpabio, to ensure it is passed.

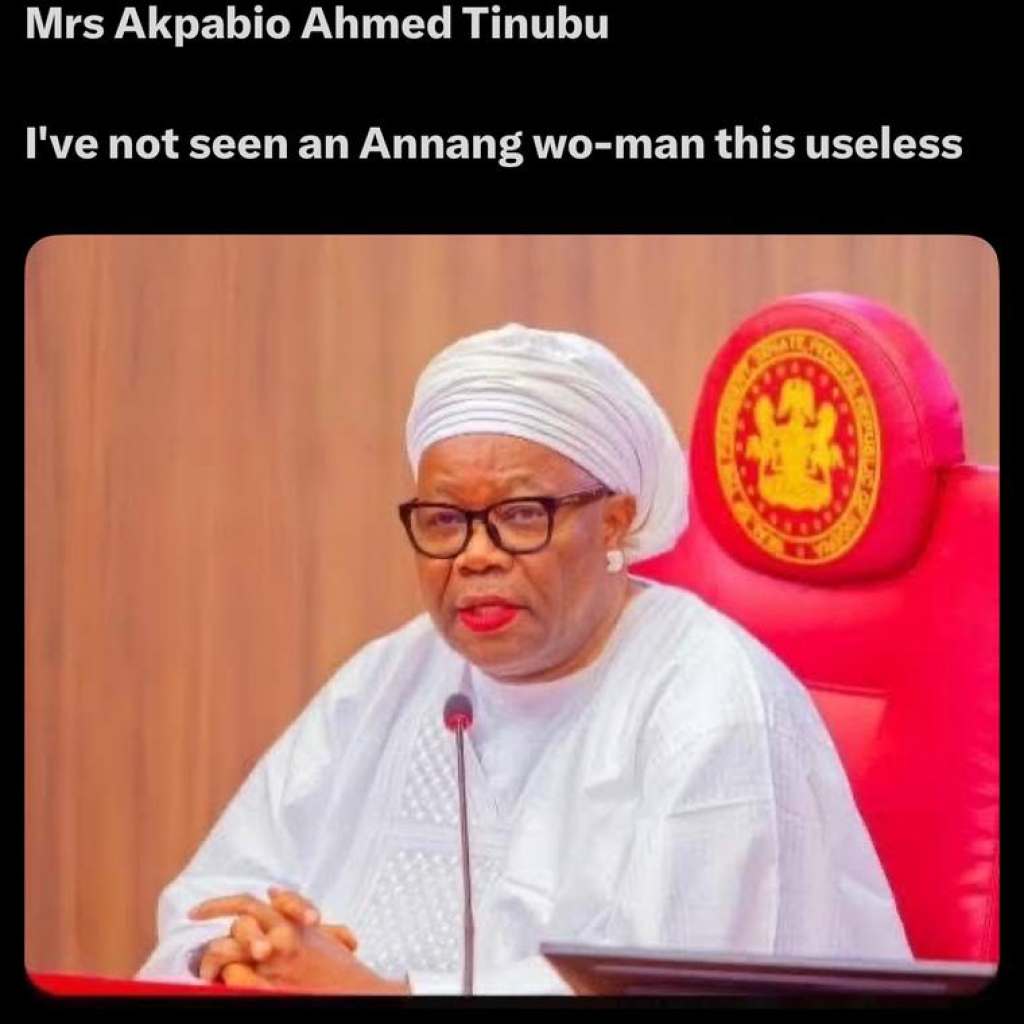

The conversation took a different turn on X formerly Twitter when a male user Son of Ayo used AI to alter the image of the Senate president putting him in a dress, a scarf and red lipstick with the caption “Mrs Akpabio Ahmed Tinubu, I’ve not seen an Annang wo-man this useless,” indirectly labelling him as a woman to buttress his perceived incompetence.

The post, which has now garnered over 1000 likes, 556 retweets and 283 comments, has attracted the opinion of other users who have critiqued the tweet, while some agree with the mockery. X user Ujubakay shared her view, stating,

“If you think he’s incompetent, say it with your chest. But dragging women into it like incompetence is feminine just shows how shallow your thinking is. A useless man is still a man… calling him a woman only makes you foolish.” Another X user, Tomiwa Tegbe, echoes a similar opinion: “A useless man is a useless man. Don’t change a man’s gender when it’s time to shame him. “Woman” is not a slur or a derogatory term for a man.”

This misogyny masquerading as political criticism implies that incompetence equals femininity, weak leadership equals womanhood, and if a male politician fumbles a legislative process, he must have become useless “like a woman.” But how can we call women incompetent when we have not given women a chance to lead?

X user, RealObasi, also replied, shedding light on women’s impact in Nigeria’s reforms,

“This is very derogatory to women. Most patriots who have carried out a great reform against all odds in Nigeria are women. The likes of Prof. Dora Akunyili.”

If incompetence were a female trait, Nigeria’s political history would look radically different, but it does not. Nigeria’s political system has been overwhelmingly male since independence. The presidency, governorships, Senate leadership, security architecture, and party structures have been dominated by men for decades. If incompetence were biological, Nigeria’s National Assembly, which has consistently had less than 10% female representation, would be the most efficient legislature in the world. Yet, the systemic dysfunction persists, signifying the male power and male failure in the old boy’s club called politics in Nigeria.

The recent uproar over the Senate’s treatment of mandatory real-time electronic transmission of election results is legitimate. Electoral credibility is the backbone of democracy. Citizens have every right to demand clarity, transparency, and legislative integrity.

But to respond to dissatisfaction by feminising a male Senate President as an insult is to replicate the same patriarchal logic that has excluded women from leadership for decades. It tells young girls watching politics unfold that “woman” is synonymous with failure. It reinforces the stereotype that political authority is inherently masculine. And it conveniently absolves patriarchy itself from scrutiny.

Men have controlled Nigeria’s political architecture since 1960. If Nigeria is underperforming economically, institutionally and democratically, the responsibility lies within male-dominated power structures. Inasmuch as many might claim that Nigeria’s political crisis is not a gender identity problem, the performance of men in Nigeria’s political space clearly means it’s time to vote for more women to hold public office; it means power must change gender.

Calling a male politician a woman when he disappoints you does not challenge that structure. It protects it. It suggests that incompetence is an aberration from masculinity rather than a predictable outcome of opaque governance, patronage networks, weak institutions, and elite impunity. If a leader is incompetent, call them incompetent. But do not call him a woman. Because womanhood is not the problem. Exclusion is.