|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

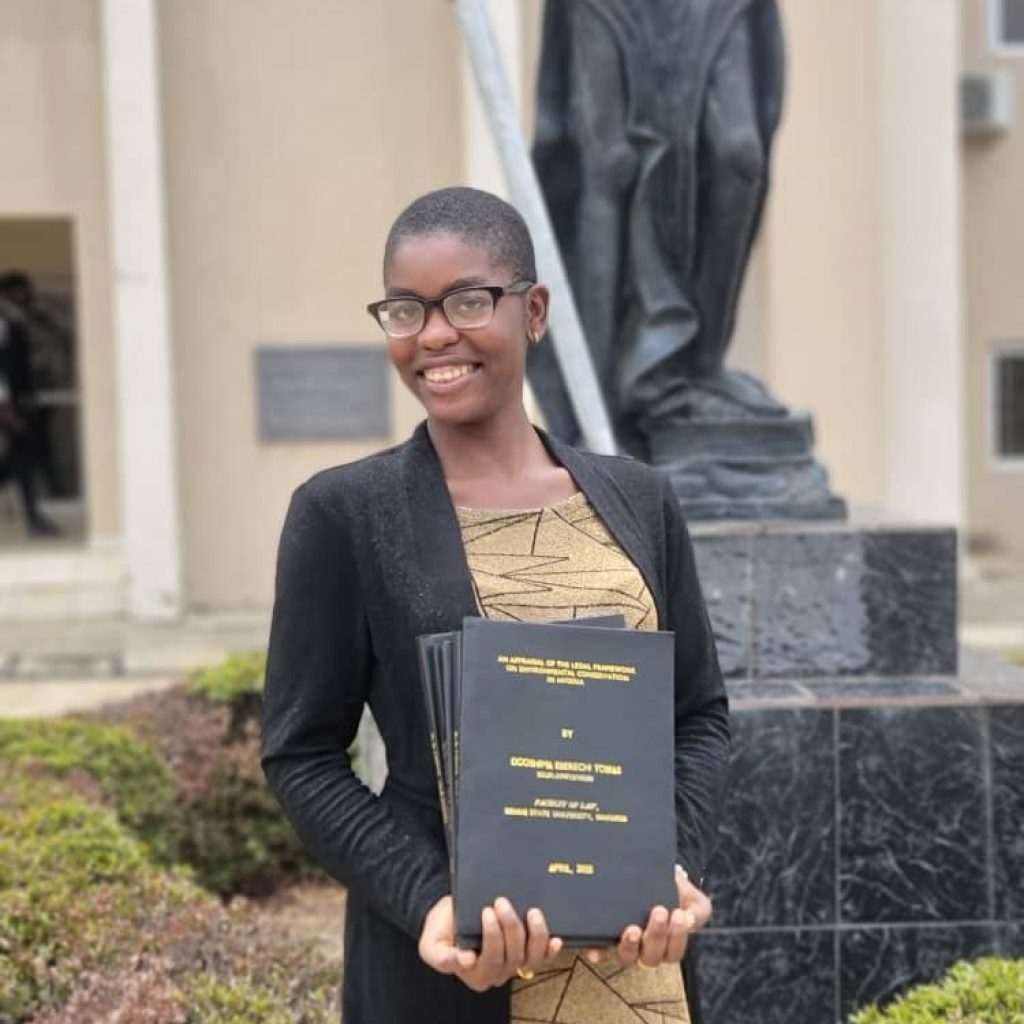

Dooshima Eberechi Tobias is a law graduate of Benue State University and an aspirant for the Bar Part II Programme at the Nigerian Law School. Currently interning at Mbafan & Co., Dooshima’s feminist consciousness has been shaped by personal experiences, family history, and the contradictions she has observed in how Nigerian society treats educated and outspoken women. In this conversation with Naija Feminists Media (NFM), she reflects on education, digital safety, poverty, and why feminist solidarity must always move beyond performance into action.

- When and how did you personally come to feminism? Was there a moment, experience, or process that shaped your feminist consciousness?

My feminist consciousness was shaped by many moments. But it probably started with my mother. Growing up with a widowed mother made me realise how much sacrifice and willpower it takes to raise children alone, especially as a very driven and outspoken woman in Nigeria.

My mother represents, to me, the African women who raise future generations — women whose labour often goes unseen and unappreciated. Reading Buchi Emecheta’s “The Joys of Motherhood” only helped solidify this thought.

I also remember a junior of mine from secondary school recounting how her aunt remained single for a long time because she had a PhD, and suitors found that threatening. I remember wondering what exactly about an educated woman was so intimidating. If I were a man, “bagging” a woman with a PhD would be a flex — so why was education suddenly a problem?

There were also the countless times people told me that wanting to be a lawyer didn’t mean I should always insist that I “know my rights,” and that this was why men supposedly don’t like female lawyers. That never made sense to me. Isn’t that the point of studying law?

So yes, it was a series of experiences that slowly but firmly shaped my feminist consciousness.

- What issues affecting women and girls are you most focused on right now, and why do you believe these issues require urgent attention?

Access to education and digital safety are the biggest issues for me right now. Education matters deeply to me because I am a product of parents who cared about my future and gave me a fighting chance in Nigeria. I am likely not hawking, doing slave labour, or destitute simply because my parents — especially my mother — prioritised her education and pursued it with determination. I once saw a quote that said, “The only reason you’re not suffering is that you won the geographic lottery,” and I’ve seen how true that is for many women. The fact that girls continue to be left behind, despite consistent reports from bodies like the UN, is deeply worrying.

Digital safety is the second issue. Gender-based abuse online has become disturbingly normalised. From figures like Kevin Samuels and Andrew Tate to countless less-visible actors, online spaces often enable hatred against women. I actually left Twitter a few years ago because it became overwhelming and contributed to my anxiety. With AI now being used to intensify this abuse, I worry deeply about what the future holds for women online.

Silencing women or forcing them to retreat from public spaces feels intentional. But opting out cannot be the solution, which is why I joined Naija Feminist Media. I believe pushing back against these narratives is necessary.

- From your perspective, which law, policy, or systemic change should be prioritised to improve the lives of women and girls, particularly in Nigeria or your community of work?

Girl-child marriage and poverty should be prioritised because they are deeply intertwined. Both are major reasons girls fail to access or complete education. Nigeria already has laws like the Child Rights Act and international treaty obligations addressing this issue, yet enforcement remains weak, especially at the state and community levels.

I was particularly disturbed to learn about “money brides,” girls given away to settle debts. Extreme poverty erodes dignity and forces families to see their daughters as commodities. Any serious effort to end child marriage must include economic interventions that support girls’ education and family survival.

Reducing poverty more broadly would also significantly improve the lives of women. While abuse cuts across class, economic pressure worsens vulnerability and normalises harmful practices. Addressing poverty is therefore essential to improving women’s outcomes.

- What does feminist solidarity and collective action look like to you, and what message would you like to share with younger or emerging feminists?

To me, feminist solidarity is practical before it is performative. Women’s struggles are interconnected, whether the issue is education, digital safety, or child marriage.

Collective action means rejecting the idea that impact depends on having a large platform. We saw this in the solidarity shown for Senator Natasha Akpoti and in the advocacy around the cases of Ochanya, Augusta, Osinachi, and others. These moments mattered because people refused to be silent. In the digital age, even a simple repost signals that injustice will not go unchallenged.

Feminist action is not new. Nigerian women have a long history of resistance, from the Aba Women’s Protest of 1929 to struggles for political representation and suffrage. Today’s digital activism is a continuation of that legacy.

My message to younger feminists is simple: speak up, no matter how small you think your voice is. Waiting for a “big enough” platform only sustains injustice. Feminist progress has always been cumulative. You don’t have to do everything, but you do have to do something.