|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Summary: Female genital mutilation remains a widespread human rights violation rooted in gender inequality, placing millions of girls at risk worldwide. Ending the practice by 2030 will require sustained commitment, increased investment, and coordinated action across governments, communities, and health systems.

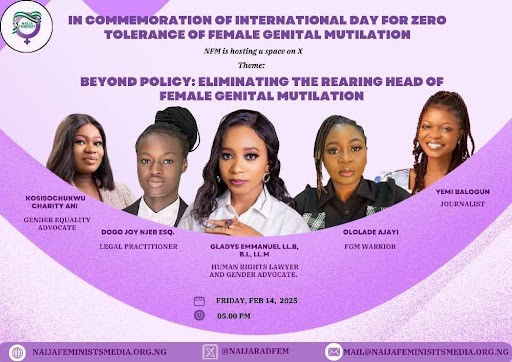

Observed annually on 6 February, the International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) provides an opportunity to assess global progress, recognise effective interventions and confront the scale of work still required to end this harmful practice. Despite years of advocacy and intervention, FGM remains a widespread human rights violation affecting millions of girls and women worldwide.

Globally, an estimated 4.5 million girls, many of them under the age of five, are at risk of undergoing female genital mutilation. If current trends persist, projections indicate that 22.7 million additional girls could be affected by the year 2030. At present, more than 230 million girls and women alive today have already undergone the practice. Beyond its human toll, FGM places significant strain on health systems, with the global cost of treating related complications estimated at no less than USD 1.4 billion annually.

For the International Day of Zero Tolerance for FGM in 2026, the global theme is “Towards 2030: No End to FGM Without Sustained Commitment and Investment.”

With only five years remaining to meet Sustainable Development Goal 5.3, which aims to eliminate FGM by 2030, the theme emphasises the urgent need for accelerated action, increased financial investment, and stronger political leadership.

The 2026 focus calls for increased funding and resources to protect the 22.7 million girls projected to be at risk by 2030. It also stresses the importance of sustained political commitment, including stronger partnerships between governments, civil society organisations, and communities. Central to these efforts is the amplification of survivor and youth voices, recognising them as critical agents of change.

Why Female Genital Mutilation is a Human Rights Violation

According to the United Nations (UN), Female genital mutilation (FGM) comprises all procedures that involve altering or injuring the female genitalia for non-medical reasons and is recognised internationally as a violation of the human rights, the health and the integrity of girls and women.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) also defines FGM as “all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.”

The practice, which is common in many African societies, has no medical benefits and causes lifelong physical and psychological harm. It violates fundamental human rights, including the rights to health, bodily integrity, freedom from violence and the ability to make informed decisions regarding sexual and reproductive health.

FGM is never safe, regardless of the setting or who performs it, and there is no medical justification for its continuation.

Types of Female Genital Mutilation

The World Health Organisation classifies female genital mutilation into four main types, all of which constitute human rights violations and forms of gender-based violence.

These include the partial or total removal of the clitoris; the removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without removal of the labia majora; infibulation, which involves narrowing the vaginal opening by cutting and repositioning genital tissue; and all other harmful procedures such as piercing, pricking, scraping, or cauterisation that serve no medical purpose.

Who is Affected by FGM?

Female genital mutilation is a global issue and has been recorded in more than 96 countries, although it is primarily concentrated in parts of Africa and the Middle East. In many of these countries, nationally representative data on its prevalence remains limited.

Girls and young women between infancy and the age of 15 are most affected, though the practice is sometimes carried out on adult women. FGM affects women throughout their lives and perpetuates broader patterns of gender inequality and violence within communities.

FGM is deeply rooted in gender inequality and sustained by complex social norms and beliefs. These include attempts to control female sexuality, reinforce ideas about modesty and femininity and mark rites of passage into womanhood.

In many communities, the practice is wrongly believed to be a religious requirement, a preparation for marriage, or a way to preserve family honour. Economic pressures, including the perception of higher dowries for girls considered “chaste,” weak law enforcement, humanitarian crises, and social expectations, further contribute to its continuation.

Health Consequences of Female Genital Mutilation

FGM is physically and psychologically harmful regardless of the age at which it is performed. It deprives girls and women of educational and economic opportunities, significantly impacts their health, and limits their ability to reach their full potential.

Physically, FGM can result in severe bleeding, infections, chronic pain, scarring, urinary and menstrual complications, sexual health problems, infertility, and the need for additional surgeries later in life. The practice carries no health benefits and is usually performed without consent, violating the right to bodily autonomy.

The psychological effects of female genital mutilation often persist throughout a survivor’s life. Many girls and women experience anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, memory loss, and reduced sexual wellbeing as a result of the trauma.

Legal and Political Developments in West Africa

In recent years, several West African countries have taken notable steps toward ending FGM. In Liberia, the President announced a permanent ban on female genital mutilation and other harmful traditional practices, reinforcing a national pledge of zero tolerance for gender-based violence.

At the regional level, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Court of Justice declared FGM a form of torture and ordered the Government of Sierra Leone to enact legislation explicitly criminalising the practice.

The theme reflects the reality that eliminating FGM within this timeframe will only be possible if political will is matched by sustained funding and long-term community engagement.

Health System Responsibilities and WHO Guidance

Preventing female genital mutilation requires long-term, multisectoral approaches, as no single intervention is sufficient. The World Health Organisation (WHO) and the HRP Special Programme emphasise the responsibility of health systems to provide person-centred, quality care for girls and women who have undergone or are at risk of FGM.

Updated, evidence-based WHO guidelines support health systems in preventing FGM by addressing medicalisation and strengthening the role of health workers in abandonment efforts. The guidelines also focus on managing health complications across the life course, providing survivor-centred sexual, reproductive, and mental health care, and strengthening health system responses in line with human rights and ethical standards.

The Way Forward

The continued prevalence of female genital mutilation, particularly across Africa, calls for the urgent need for coordinated and sustained action. Governments, non-governmental organisations, health systems, and communities must work together to raise awareness, strengthen and enforce legal protections, and provide comprehensive support for survivors.

By amplifying survivor voices and fostering cultures that respect the health, dignity, and rights of girls, it is possible to move toward a future free from FGM. With sustained commitment, adequate investment, and collective action, future generations can live without the fear and lifelong consequences of this harmful practice.