|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

In Nigerian digital spaces, moral policing has become naturalised, with many discourses centring on what a female can and can’t do on social media. This is no different from colonial times, when women’s bodies were held to moral standards. “That skirt is too short.” “Why are you dressed like that?” and it worsens when the woman is married. “Why would a married woman dress like this? Have you no respect for your husband?”

The debate on female autonomy in marriages is inexhaustible, as not only are marriages in our society biased—stripping women of protection while shielding men—they also serve as the hallmark excuse for moral policing.

Within the last two months, several women have been made a spectacle by many tweeps on X. From Mizel, who was vocal about her sexuality, to the slut-shaming of engaged female partners by alleged ex-lovers/sex partners, women’s timelines have been turned into courtrooms, with their bodies as the centre of discourse. The question is, “Is policing done to protect values, as tweeps often argue, or to punish women?”

Moral policing, an arm of patriarchy, is the act of enforcing societal moral codes, often informally, by criticising, shaming, and punishing individuals whose behaviour is seen as “immoral” or socially unacceptable. A common example in recent times is the issuance of repressive dress codes to female students in universities. A viral video from Olabisi Onabanjo University showed females being searched to ensure they wore bras, with denial of entry into the exam hall as punishment.

Slut-shaming, an offshoot of moral policing, is the act of criticising and insulting someone, usually a woman, for behaving in ways perceived as sexually provocative or expressive, such as dancing or speaking boldly about sex. It exists to ensure control and punishment of women while excusing men.

A popular analogy goes thus: “A key that opens all locks is a master key, while a lock that can be opened by all keys is a bad lock.” This sexist analogy, depicting women as locks and men as keys, captures society’s hypocritical moral code.

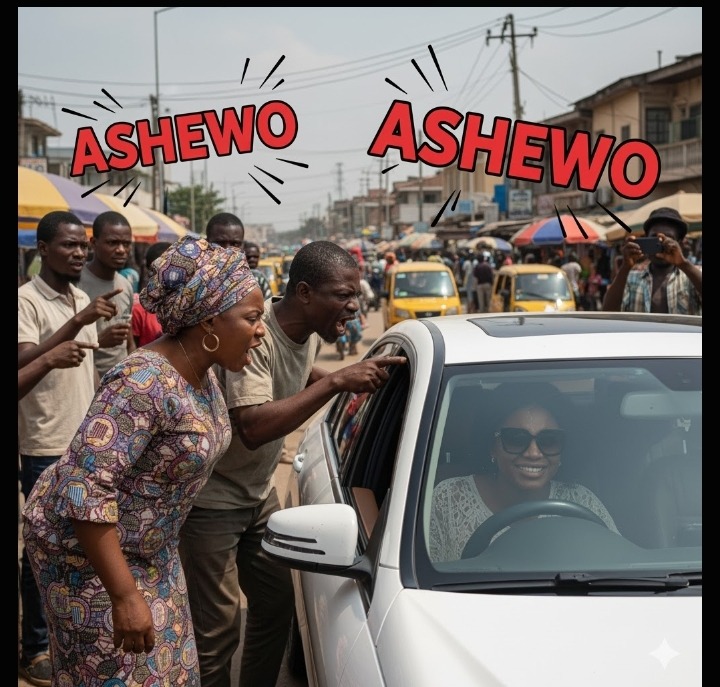

By this, it accepts and hails male sexuality while punishing and silencing female sexuality. It also emphasises the male–female sexual dynamic by reinforcing the notion that women belong to their men and should gatekeep themselves—“keep” themselves for men only. A woman who does otherwise thus becomes a bad woman; an ashewo, who should then be ostracised, criticised, and remain unmarried as penance for her crime against morality.

In the Nigerian X space, moral policing and slut-shaming have taken a worse turn. Tweeps police without guns and faces. They use shame as a baton to discipline an “erring” woman while justifying it with “decency.” And if she remains unyielding, they threaten her with the ultimate bullet—marriage. “Who will marry this one?” “I pity who will marry this one,” they sneer, all as a means to control women.

When Mizel, an X user, got married despite her notable sex conversations, the moral police on X nearly ran amok. It was an abomination for a woman like her to be rewarded with marriage despite her “indecency.” They slut-shamed and body-shamed her, and when that didn’t ruin her marriage, they called her husband a “simp,” among other names.

Similarly, a young X user posted a photo of his fiancée, and another male user commented on how he had previously “patronised” her to shame and ruin the relationship. The goal was to ensure the punishment of a woman for daring to have a sexuality by ensuring she isn’t rewarded with marriage, which, in their view, is only deserved by “good” women.

Moral policing, although often championed by men, doesn’t absolve women from the act. Women like Chioma Oji, a physics scholar, are known for slut-shaming women. From calling saidaboj an ashewo and releasing a diss track, she reinforces the quest for “good womanhood” and virtuousness. Women like Chioma Oji, male-centred women, have, out of delusion, believed that by playing everything right according to moral standards, they are absolved from the commodification of other women. The belief that she wasn’t like other women, based on her academic standards, fueled her drive as an unpaid enforcer of moral codes until she was called an ashewo, the same degrading name she used on another woman, and lost it.

Male-centred women who believe they’re “not like those ones” forget that proximity to men has never saved any woman. And being hardworking doesn’t exempt one from slut-shaming. A woman is slut-shamed for speaking openly about sex, and another is slut-shamed for buying a car or being successful. Moral policing was never about decency. It is deeply rooted in control. Every time a woman asserts autonomy, either sexually or financially, society flags it as rebellion, a deviation from the laid-out blueprint for women, and quickly swings into action by criticising, insulting, shaming, and threatening her to conform.

Female freedom is viewed as a disruption of societal order, and like every oppressive system, it relies heavily on force. The moralisation of women stems from the need to ensure women stay down and continually look up to men. It twists respectability into the honour a woman must strive for, while ensuring that, regardless of her actions or inactions, she remains just an extension of men. The respectability of a woman is thus based on the men in her life. Nigerian social media is merely a reflection of a society that thrives only by repressing half of its population. It amplifies the offline policing of women through hashtags, takes, shades, and draggings.

And just like that—without guns or badges, without stations or resources—moral police shoot at the assertion, opinion, and freedom of women, ensuring their silence online. This highlights how fragile our “over-exaggerated gender equality progress” truly is. Women can now go to school, but must not have an opinion. Women may work, but must not be wealthier than men. Women may have sex, but must be ashamed and live forever regretting it. Women can lead, but only in ways that suit men.

Editor’s note: Nusrat Lasisi is a women’s rights activist, creative writer and student. She can be reached via email at nusratlasisi2000@gmail.com, Facebook, Instagram, and X (Twitter) at @nusratdreteller.